Archived - Pandemic H1N1 2009 Pig Farm Outbreak - CFIA Lessons Learned

This page has been archived

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

March 2011

Management Response

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Introduction and Methodology

- 3. Background and Chronology

- 4. Summary Event Chronology

- 5. CFIA's Preparedness and Response

- 6. Coordination With Stakeholders

- 7. Positive Outcomes

- 8. Conclusion

- 9. Recommendations

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

Acknowledgements

The pandemic H1N1 outbreak in 2009 led to a number of lessons learned documents from various government departments, including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and Health Canada, which were used in preparing this report.

1. Executive Summary

The pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) outbreak at a pig farm in Alberta in 2009 occurred at the same time as the first cases were being confirmed in the Canadian population, and before there was any knowledge of the relatively low mortality rates in animals and humans. Owing to the heightened concern at the time, combined with limited knowledge of the risks posed by the virus, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) adopted a precautionary approach and quarantined the farm.

At the national level, the emergency was managed effectively by following well documented procedures and policies. Communication and coordination with stakeholders was both effective and efficient. At the regional level, some challenges were encountered initially when untrained inspectors were sent to collect the initial samples and deliver them to the laboratory. The use of untrained personnel pointed to a lack of knowledge of emergency response procedures, not only among the inspectors, but also among the managers and supervisors involved. This situation was also linked to a lack of consultation with occupational health and safety advisors. Emergency response training would also have helped to ensure that employees potentially exposed to the virus would not be involved in the delivery of samples. While training has since been made available, it remains ad hoc.

2. Introduction and Methodology

The CFIA routinely conducts lessons learned or post incident reviews following exceptional situations in order to assess the relevance and effectiveness of policies and procedures, and to identify what worked well and what needs improvement.

The CFIA has dealt with a number of animal health emergencies since 2003 when the first BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) case occurred. Since that first large scale emergency, the CFIA has had the opportunity to learn from experience and make improvements to its emergency response activities including planning, logistics, communications, information for decision making, and occupational health and safety. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic, however, presented unique challenges including the risk of human to animal transmission. The potential threat to human health from infected swine was also a concern, as was the impact on the pork industry when countries began imposing trade restrictions on Canadian exports.

This review was carried out between June and November 2010, based on analysis of documents and interviews with 36 CFIA staff members and managers, and provincial and industry representatives in Alberta, Winnipeg, and Ottawa.

3. Background and Chronology

In early spring 2009, frequent media reports identified the potential for a pandemic flu outbreak, originating in Mexico. Concern was heightened by a lack of scientific data on the effects of the virus. On April 24, 2009, media reports revealed the high level of concern at the World Health Organization (WHO):

Heightened anxiety was also apparent among WHO officials in Geneva. The organization activated its 24 hour emergency operations centre Friday [April 24, 2009]. Both Canada and the U.S. have activated theirs as well. It wasn't clear when the decision would be taken on the pandemic alert level, though experts expect events to move quickly in the coming days. "We're very concerned. And this is why we're running our operations centre 24 hours a day and why the DG (director general) is moving to call the emergency committee… It all indicates the very high level of our concern," said Gregory Hartl, a spokesperson for the organization.Footnote 1

The pH1N1 virus spread quickly. On April 26, 2009, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) confirmed the first six human cases of pH1N1 infection in Canada; on May 2 it confirmed 55 cases; on May 14 there were 449 cases; and by May 25 there were 921 cases and two deaths confirmed in Canada. On June 11, the WHO declared the first pandemic in 41 years as the virus had spread to numerous countries.

The CFIA and PHAC responded in a proactive manner. On April 20, 2009, PHAC began monitoring the investigation of the outbreak of Severe Respiratory Illness clusters in Mexico and human swine influenza cases in the United States. On April 23, PHAC activated its Emergency Operations Centre and the CFIA identified a liaison officer to PHAC. Considering that an estimated 65 to 80 percent of newly identified human diseases are zoonoticFootnote 2, the Mexican and U.S. evidence of swine influenza cases made this inter-Agency coordination imperative. On April 24, the CFIA asked provincial chief veterinary officers to inform swine producers of the need for enhanced biosecurity and reporting. (See Appendix A for the detailed chronology of events.)

On April 28, Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD) informed the CFIA about a possible pH1N1 outbreak at a pig farm in central Alberta. The only federally reportable influenza is Notifiable Avian Influenza (H5 or H7) in poultry, and then only if it is highly pathogenicFootnote 3. However, because of the unknown nature of the risk the virus posed to swine and human populations, the CFIA took a precautionary approach and quarantined the farm, plus an associated farm, following consultation with the province.

One of the CFIA inspectors who took the initial samples travelled by commercial airline the following day to deliver the samples to the CFIA's laboratory in Winnipeg. Both inspectors were later confirmed to have contracted the virus.

It was soon determined that the virus presented a low risk to both humans and pigs; however, the CFIA had difficulty determining the criteria to lift the quarantine, and the markets for the pigs had closed, as was noted by Canada's Chief Veterinary Officer:

…it became difficult for the CFIA to modify the initial precautionary approach and identify alternate criteria for the release of the quarantine. In spite of clinical recovery and negative status of market weight animals, market forces resulted in there being no slaughter facility willing to receive the animals.Footnote 4

Without any market for the pigs, the Alberta farm decided to have the entire herd of more than 3,000 culled.

4. Summary Event Chronology

(Detailed Chronology located at Appendix A)

- April 28, 2009: CFIA is informed by Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD) of a possible pandemic H1N1 influenza outbreak at a pig farm in central Alberta

- CFIA quarantines two farms and takes samples

- April 29: One of the inspectors involved in the sampling transports the samples by commercial airline to Winnipeg (National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease, NCFAD)

- May 1: NCFAD initial results confirm that the virus in the swine herd is an influenza A virus of an H1 type.

- 16 countries close their borders to all Canadian pork products

- May 5: NCFAD confirms the virus found in the pigs is the same as the novel pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus causing illness in humans around the world

- June 7 - 8: Herd is culled by AARD at the request of the farm

- July 29: The quarantine is lifted following CFIA confirmation that the site has been disinfected

5. CFIA's Preparedness and Response

A) The CFIA was mostly well prepared

The CFIA was mostly well prepared for the outbreak. Before AARD informed the CFIA on April 28, 2009, of the outbreak at the pig farm, the CFIA identified its liaison officer to PHAC (April 23). Four days prior (April 24) to notification of the outbreak, the CFIA briefed provincial chief veterinary officers on the need to inform swine producers about enhanced biosecurity and reporting requirements. One day prior to notification of the outbreak, the CFIA fully activated its National Emergency Response Team (NERT) and National Emergency Operation Centre (they had been partially activated on April 20).

Roles and responsibilities for CFIA staff responding to this incident were, for the most part, well understood and followed. On May 6 and 20, 2009, NERT members and others involved in the outbreak met to discuss what aspects of the CFIA's response were effective and what aspects still needed improvement. This "hot wash" process has become routine in the Agency and is identified in its Emergency Response Plan as a "critical step". The hot wash noted that some improvements were needed to increase information sharing internally, including a review of distribution lists, and other issues related primarily to refining existing processes. Sufficient guidance appears to be provided in procedure manuals and plans, such as the CFIA's National Logistics Emergency Management Plan, the CFIA Emergency Response Plan and the Animal Health Functional Plan.

The release of the antiviral Tamiflu was also identified as an area for improvement. Two issues were raised here: that of access to the antiviral from PHAC, and that of its provision to employees. The former issue has since been resolved since the CFIA now has authority to access Tamiflu without first obtaining Health Canada concurrence. The second issue was addressed in the November 2010 outbreak of Notifiable Avian Influenza on a turkey farm in Manitoba, where staff were no longer required to take Tamiflu to access the site, owing to concerns raised regarding the antiviral's safety and efficacy.

Many of those interviewed for this report identified the Agency's experience with Avian Influenza outbreaks as having provided substantial experience in similar emergency response situations, helping the Agency to be well prepared for this outbreak. That previous outbreaks have significantly improved CFIA's preparedness for animal health emergency response was noted in Chapter 9 (Animal Diseases) of the Auditor General of Canada fall 2010 report.

B) Weakness in the use of the Incident Command System

Some weaknesses were noted in the Incident Command System (ICS).

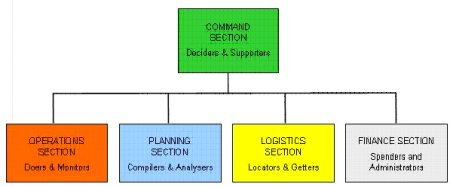

The Incident Command System, or ICS, is a standardized, modular, all-hazard incident management concept. The Agency's emergency response structures are organized around ICS's five management functions (Command, Operations, Planning, Logistics, Finance and Administration) as depicted below:Footnote 5

Click on image for larger view

Incident Command System

Connected to a box containing Command Section (Deciders and Supporters) are four boxes from left to right containing the following:

- Operations Section (doers and Monitors)

- Planning Section (Compilers and Analysers)

- Logistics Section (Locators and Getters)

- Finance Section (Spenders and Administrators)

The Occupational Health and Safety (OSH) advisor position is situated within the ICS Logistics Section (facilities, services and materials), which means that the position does not provide direct advice to the incident commander (Command Section), a situation that may not support optimal effectiveness. Unless the OSH advisor is made aware of events as they unfold, it is difficult to ensure that the incident commander is advised of OSH considerations. The OSH advisor is less likely to be kept informed of events if the position reports only to the head of the Logistics Section.

At the start of the outbreak, incident commanders at the regional and field levels did not obtain OSH advice. The OSH advisory role was placed in the Command Section in the regional ICS organization chart created ten days after the event began. (Please see Appendix B for organization charts.)

Meanwhile, the NERT organization chart places OSH under Care of Personnel (eg, travel arrangements, etc), which is part of Logistics. There is a clear relationship between OSH and care of personnel, but the lack of a direct advisory link to the incident commander in such situations reduces both the visual reminder and the accountability for incident commanders to keep their OSH advisors informed of events and to seek their input. The CFIA's Participant Manual for its course entitled "Introduction to the Incident Command System in the CFIA" describes the OSH Officer as "a member of the Command Staff."Footnote 6

C) Lack of training and awareness of need for training

Neither the field inspection manager nor the CFIA veterinarian chose to use trained staff to take the initial samples. While both inspectors involved had received training in sampling procedures, neither was trained in the use of personal protective equipment to work in a potentially infectious area, or "hot zone." Trained staff were available at both the regional head office and the neighbouring regional office, each roughly two hours drive from the field office in Red Deer. Waiting for inspectors to arrive from one of the regional offices could have delayed the initial sampling to the following morning (April 29).

Area management informed the field office in Red Deer on the afternoon of April 28 of the suspected outbreak and the urgency of quarantining the farm, obtaining samples and delivering them to the Winnipeg laboratory (National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease or NCFAD). The CFIA District Veterinarian in charge of taking the samples was familiar with the farm and aware of illnesses among the herd there that showed influenza-like symptoms. Swine flu is common on swine farms and generally is not zoonotic.Footnote 2 Therefore, he did not believe pH1N1 would be found at the farm. He chose to use the only inspectors readily available to take samples that evening (April 28), inspectors who had not had training in the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Proper bio-containment procedures were not followed by the inspectors and veterinarian while taking the samples.

The next morning, the samples needed to be delivered to the laboratory in Winnipeg. A courier service would not have been able to deliver the samples to the lab until the following day, so one of the inspectors who had taken the samples the previous evening was asked to take the samples aboard a commercial flight (as checked baggage), to ensure the samples arrived the same day. By this time (on the morning of April 29), both inspectors were complaining of sore throats, which was attributed to the high level of ammonia and dust in the pig barn that they had breathed in without wearing proper masks. It was confirmed within two weeks (May 8 and 11) that both inspectors who carried out the initial sampling were infected with the pH1N1 virus. On the morning of April 29 the veterinarian who supervised the inspectors during sampling was still convinced that pH1N1 was not present, because of the low mortality seen in the barn, and in turn field management did not consider the possibility that the inspectors were infected.

Improper use of PPE by the field inspectors made it impossible to rule out the pig farm as the source of their infection with pH1N1. Training would have increased the likelihood of proper use of PPE and ensured better awareness of the risks associated with allowing one of the inspectors to take a commercial flight to deliver the samples. Consultation with an OSH advisor would have increased the likelihood that the manager and the veterinarian in charge would have been made aware of the risk associated with using untrained staff and sending one of them on a commercial flight.

Past internal reviews have identified the need for training. The CFIA's 2004 and 2007 Avian Influenza Lessons Learned reports noted that biosafety training and exercises are crucial and they recommended an increase in that type of training. For example, the 2007 report (Lessons Learned Report: The CFIA'S Response to the 2007 Avian Influenza Outbreak in Saskatchewan) stated:

Previous training and experience with the Incident Command System among key personnel, through a combination of experience gained in the B.C. outbreak and subsequent field exercises was vital to the smooth functioning of operational commands during the emergency.

The report's fifth recommendation was that "CFIA should increase staff training efforts to help ensure adequate succession planning for future outbreaks." The 2004 report (Lessons Learned Review: The CFIA's Response to the 2004 Avian Influenza Outbreak in B.C.) also identified training as a key to enhancing emergency preparedness in the Agency:

Additional training of CFIA and industry personnel in bio-safety and bio-security was identified as a means to enhance personal protection and improve the effectiveness of bio-security measures and protocols … Ongoing training and exercises were recognized as being key to improving knowledge of emergency response plans and protocols, as well as building relationships between the CFIA and its partner organizations.

The CFIA's 2010 Evaluation of the Avian and Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Initiative underscored the lack of training exercises since 2008.Footnote 7

At least one external report has underscored the importance of emergency response training for the CFIA. The lessons learned report commissioned by the Canadian Swine Health Board in connection with the closure by the CFIA of a meat packing plant in Alberta: Lessons Learned: A Review of the Animal Health Investigation at Red Deer, Alberta, June 21-23, 2010 recommended that "…CFIA continue to provide appropriate training and back-up expertise to local CFIA decision makers…to ensure a high priority is placed on this training and provision of backup expertise in the future."Footnote 8

The CFIA's National Logistics Emergency Management Plan commits the Agency to provide training and exercises:

The CFIA is required under the Emergency Management Act to conduct training and exercises for the emergency plans within its mandate. Exercises provide an opportunity to perform emergency duties in response to a simulated event and to enhance the competence of emergency responders.Footnote 9

In its Personal Protection Directive, the Plan outlines the requirement that the Agency provide PPE training when necessary:

The Canada Labour Code (CLC) Part II, the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Part XIX and the CFIA OHS Policy require that CFIA when necessary, develop, implement and monitor a program for the provision of personal protective equipment, clothing, devices or materials (PPE).

While the CFIA requires relevant branches to develop their own Personal Protection Programs, they are required to include "…Training including fit testing, safe use and maintenance."

On site and in-class training was made available to relevant CFIA employees in January 2010 with federal pH1N1 emergency funds. The frequency of this training remains at the discretion of area and regional management.

6. Coordination With Stakeholders

A) Industry

The Canadian Pork Council noted that communication with the CFIA during the outbreak event was timely and coordination was effective.

B) Provincial

The CFIA worked closely with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD) from the outset, maintaining open and effective communications. However, there appeared to be some room for improvement when it came to understanding roles and responsibilities related to the cull.

Due to the privacy of individual health information, CFIA staff are not always made aware of the infected status of co-workers or other people (e.g., farm families) they may come into contact with when handling outbreaks. Ensuring this privacy is the responsibility of provincial health authorities. Privacy issues can create challenges for an employer like the CFIA in terms of ensuring the safety of the staff involved in outbreak response.

C) Public Health Agency of Canada

The CFIA'S representation on PHAC'S emergency management team prior to the outbreak supported the timely sharing of information. Furthermore, the CFIA'S scientific risk assessment work with PHAC is a positive outcome as outlined below.

7. Positive Outcomes

A) Expedited coordination with PHAC on risk assessment

The pH1N1 situation has led the CFIA to reinforce the collaborative approach in the assessment of animal health and public health risks in zoonotic diseases, including the identification of processes and policies for future assessments. During the outbreak in Alberta, the CFIA, in collaboration with PHAC, undertook an evaluation of risks arising from pH1N1 virus via release and exposure pathways, in connection with domestic mammals and birds, and a discussion of potential consequences and impacts on animal health associated with direct and indirect impacts on market access. The resulting Risk AssessmentFootnote 10 report noted that "Acknowledging the importance of an integrated approach with public health, this assessment will consider the risk of dissemination of virus to humans." This CFIA PHAC collaboration led to significant exchange of information, co operation in terms of expertise, risk assessment sharing and integration

This contributed to the response to a 2008 OAG recommendation for such joint work and process development between PHAC and the CFIA, which both agencies had already planned.Footnote 11

B) Heightened awareness of need for preparedness for zoonotic outbreaks

The outbreak raised discussions among those representatives of the Security and Prosperity Partnership (United States, Mexico and Canada) who manage the North American Plan For Avian & Pandemic Influenza, around coming to terms with public health government expectations for how departments of agriculture will meet their needs for enhancement of public health science through direct enhancement of swine surveillance.

8. Conclusion

Coordination and open, and immediate communication with all relevant stakeholders supported the successful management of this emergency animal disease outbreak. Existing procedure manuals and processes, and the experience of CFIA staff and management with past outbreaks provided a foundation of preparedness that served the Agency well during this outbreak. However, the use of untrained staff and the failure to fully consider occupational health and safety in initial decisions led to a breakdown in safety that raises concerns regarding the preparedness and awareness of those employees who may be called on to manage and respond to a disease outbreak in future.

9. Recommendations

It is recommended that:

- Operations Branch ensure that its front line responders to animal health emergencies have the relevant emergency response training including familiarity with the requirements of protocols, directives and guidelines on the use of personal protective equipment and the shipping of biological samples, and;

- An occupational health and safety advisory position be located at the Incident Command level for all suspected zoonotic outbreaks.

Appendix A

Detailed Event Chronology

- April 20, 2009: PHAC begins monitoring the investigation of human swine influenza cases in the United States

- The CFIA partially activates it National Emergency Response Team (NERT)

- April 23: CFIA identifies a representative for PHAC's Emergency Operations Centre

- April 24: CFIA asks provincial chief veterinary officers (CVOs) to inform swine producers about the need for enhanced biosecurity and reporting

- April 26: First cases (6) of confirmed human swine flu in Canada announced by PHAC

- April 27: CFIA fully activates its National Emergency Response Team

- CFIA planning cell conference call to discuss policy position if outbreak found at a pig farm

- April 28: CFIA informed by Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD) of a possible pandemic H1N1 influenza outbreak at a pig farm in central Alberta.

- CFIA quarantines the farm and an associated farm and takes samples

- April 29, 2009: One of the inspectors involved in the sampling transports samples by commercial airline to Winnipeg (National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease or NCFAD) to ensure fast delivery

- Both inspectors who took the initial samples report having sore throats

- April 30: CFIA informs industry stakeholders and provincial CVOs of possible outbreak on pig farm

- May 1: NCFAD initial results confirm that the virus in the swine herd is an influenza A virus of an H1 type

- 16 countries close their borders to all Canadian pork products

- May 2: CFIA issues public announcement that a swine herd in Alberta is infected with the pandemic H1N1 flu virus

- 55 human cases of infection confirmed in Canada (449 cases by May 14)

- May 3: The CFIA lifts the quarantine on the associated farm

- May 5, 2009: NCFAD confirms the virus found in the pigs is the same as the novel pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus causing illness in humans around the world

- May 6 - 8: CFIA working with AARD, PHAC and HC. HC prepares to administer Tamiflu to CFIA sampling staff

- Cull of some of the herd (467) due to overcrowding. Culled animals rendered and buried

- 2 to 3 weeks of sampling planned to prove virus is no longer present in herd. This is pre requisite to lifting quarantine

- June 5: Due to the refusal of processors to accept the pigs for any markets, the producer requests that CFIA cull the herd, but CFIA has no reason to order cull (no health threat) so the province agrees to cull the herd

- June 7 - 8: Herd is culled by AARD at the request of the farm

- July 29: The quarantine is lifted following CFIA confirmation that the site has been disinfected

Appendix B

Organization Charts

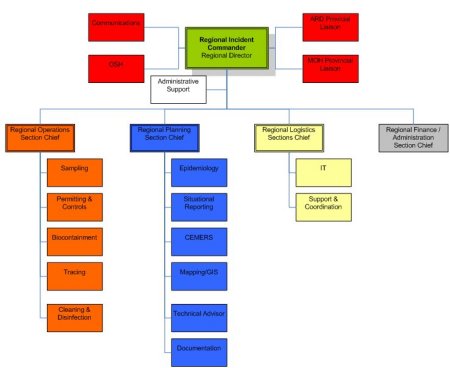

Click on image for larger view

Alberta North Regional Incident Command System

In the center of this chart is a box containing Regional Incident Commander Director. Stemming from this box are 5 boxes, 2 boxes to the left contains Communications and the other contains OHS. Two boxes to the right contain AARD Provincial Liaison and the other contains MOH Provincial Liaison. The fifth box contains Administrative Support.

Connected to Administrative support are four sections:

- Regional Operations Section Chief with subsections: Sampling, Permitting and Controls, Biocontainment, Tracing and Cleaning and Disinfection

- Regional Planning Section Chief with subsections: Epidemiology, Situational Reporting, CEMRS, Mapping / GIS, Technical Advisor and Documentation

- Regional Logistics Sections Chief with subsections: IT and Support and Coordination

- Regional Finance/Administration Section Chief

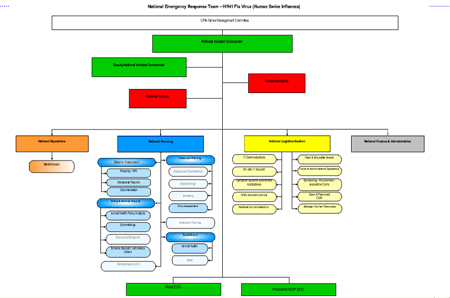

Click on image for larger view

National Emergency Response Team - H1N1 Flu Virus (Human Swine Influenza)

CFIA Senior Management Committee is connected to National Incident Commander, which then branches off into 3 different sections: Deputy National Incident Commander, National Liaison and Communications.

Following are four major subsections, each containing their own subsections.

From left to right

- National Operations with subsection: Border Issues

- National Planning with subsections: Situation Assessment (Mapping/GIS, Situational Reports, Documentation), Policy and Science Support (Animal Health Policy Analysis, Epidemiology, Biosecurity Measures and Science Support/Laboratory Liaison,), Demobilization Unit, Advanced Planning (Disease and Surveillance, Epidemiology, Modeling and Risk Assessment) and Resource Planning, Trade Branch (Animal Health and Meat).

- National Logistics Section with subsections: IT Communications, On-Site IT Support, Computer Systems and Business Applications, NHQ Accommodations, National Accommodations, Fleet and Moveable Assets, Travel and Administrative Operations, Contracting/Procurement/Acquisition Cards, Care of Personal OHS and Strategic Human Resources.

- National Finance and Administration

Below this are two boxes that are connected back to the second box "National Incident Commander" are West EOC and Pandemic BCP EOC.

- Date modified: