Archived - Evaluation of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Program

This page has been archived

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction and Context

- 2.0 Methodology

- 3.0 Key Findings

- Annex A: A Profile and description of Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Safety and Quality Program Context, Activities and Issues

- Annex B: The FFVP Results Logic and Systems Performance Framework

- Annex C: Evaluation Approach

- Annex D: Risk Management and Outcomes-Based Standards: A Review of International Experience Related to Food Safety

- Annex E: Interview Guides

- Annex F: Evaluation Matrix

- Annex G: Bibliography

Executive Summary

The need for an internal evaluation of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP) was identified in the CFIA's Evaluation Plan (2012-2017), approved by the Evaluation Committee in June 2012. The FFVP falls under Program Activity 1, Food Safety Program in the CFIA's Program Alignment Architecture (PAA) which links to the overall strategic outcome of having a safe and accessible food supply and plant and animal resource base.

This evaluation examines the FFVP's relevance and performance during the period from 2008 to 2013, with respect to the Program's two foci:

- food safety goals; and,

- food quality, related to marketing and market access

At the request of senior management, this evaluation also examines the implications of the past and present with regard to future directions, including current Safe Food for Canadians Action Plan and Inspection Modernization (IM) initiatives.

For the purposes of this evaluation, the FFVP consists of all areas in the Agency that address fresh fruit and vegetable issues, whether housed in Policy and Programs, Operations or Science Branch.

Relevance

Document reviews, a literature review and interviews and consultations with key informants suggest that the FFVP is relevant to the food safety needs of the FFV sector. However, its inspection activities focus heavily on serving market access and quality needs.

Systematic risk assessments worldwide and key informant interviews suggest that there is a strong need for a regulatory program devoted to food safety in the FFV sector. International agreements related to specific commodities continue to require grading and other quality-related support. This suggests a need for some form of market access support.

A review of documents shows that the FFVP's food safety objectives clearly align with federal government priorities, as set out in the Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA), Inspection Modernization (IM) initiative and with Agency strategic outcomes. The support for market access is explicit in current regulations. Once in force, the Safe Food for Canadians Act will provide authorities for regulations to support trade. Support for market access is indirectly aligned with the Agency's current strategic outcomes.

Up to now, the CFIA's main FFV safety role, responsibilities and activities have been oriented to selective monitoring, reaction and remediation, as there are no comprehensive federal food safety regulations in this sector that would facilitate robust establishment-based risk analysis and oversight. Furthermore, the CFIA's main active FFV role to date, as shown by delivery activities and resource use, has been to support market access. The FFVP has a long standing history oriented to market access, beginning with grade standards in the 1930s. Implementation of the SFCA is expected to significantly strengthen the food safety aspects of the FFVP, through the implementation of preventive food safety regulations.

All evidence clearly suggests that the FFVP will need more resources in order to deliver on its quality aspects. Similarly, considerable new resources will be required to achieve the identified food safety objectives for this sector. Considerable effort will need to be spent on repositioning the Agency with FFV stakeholders, who have historically seen the CFIA primarily as an enabler in securing market access, rather than providing regulatory oversight to meet food safety objectives. The evidence further suggests that a number of fundamental Program foundations, which are necessary for implementation of the SFCA and IM food safety agendas, have not yet been developed. These include knowledge of industry players and associated risks, as well as a shared understanding with all stakeholders of outcome-based FFV safety requirements. Factors relating to broad socio-economic and historical conditions, regulatory instrument requirements, governance and management and the engagement of regulated parties, present particular challenges that are expected to create a difficult context for CFIA's planned transition. A FFVP pilot project conducted from 2010 to 2012 saw inspectors across the country inspecting vegetable establishments for the first time. Many of the inspectors were not prepared to undertake this new work in the area of safety when they had only been involved in supporting market access up to that point. A great deal of communication, engagement and training is deemed necessary in order to undertake such work in future.

Performance

Evidence suggests that industry requirements and private sector programs play a stronger role in influencing FFV safety than existing CFIA program activities. Industry leadership for food safety is appropriate and expected, as the safety of its products are its responsibility. In the case of the FFV sector, the food safety role of the CFIA has been particularly weak because of the absence of a comprehensive CFIA FFV food safety program, including preventive food safety regulations and extensive sampling and testing.

CFIA activities for produce safety are reactive and focus on limited national sampling and testing programs for hazards. As a result, there is insufficient evidence to conclusively state to what degree FFV products in Canada are safe. However, it should be noted that there is a large body of evidence, both from the literature and from domestic surveillance, monitoring and studies, indicating that fresh fruits and vegetables are increasingly becoming a food safety concern.

The FFVP quality and market access activities have successfully supported the sector's needs, though some concerns have been raised regarding the Agency's resource limitations and, given these limitations, its allocation of resources between safety and market access.

There is no consistent accounting of resource investments in key FFVP activities and, as a result, the Program's economy and efficiency cannot be calculated or demonstrated.

The findings from the evaluation suggest that the CFIA will face many important challenges to integrate FFV components and stakeholders into a single food safety program by 2015-16, when the SFCA is planned to come into force. In order to support the FFV food safety and quality objectives, the CFIA should consider the following key recommendations.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The CFIA should:

1a) critically review the existing regulatory framework, particularly relating to trade, marketing and grading requirements, to ensure alignment with FFV sector policy objectives;

1b) clearly identify CFIA and stakeholder (e.g., provincial governments, industry federal government departments) roles and responsibilities in achieving FFV safety and trade/marketing objectives, particularly considering whether there are opportunities for the CFIA to transition out of some or all of the non food safety related activities; and

1c) identify resource requirements to deliver on these objectives, recognizing the resource gaps that currently exist for delivery of the existing FFV Program for both safety and quality.

Recommendation 2

The CFIA should develop and implement a performance measurement strategy for the FFV components of the new Food Program as a foundational element to program design and ongoing monitoring of effectiveness. This FFV focused PM Strategy should be integrated into the overall Food Program PM strategy.

Recommendation 3

To support the implementation of the SFCA, the CFIA should develop a targeted engagement strategy for the FFV sector that recognizes the distinct features and relationship challenges to this sector. This should particularly recognize the new risk-based food safety oversight for this sector which will represent a fundamental change from the current service orientation to facilitate trade.

List of Abbreviations

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- CAPA

- Canada Agricultural Products Act

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- CPLR

- Consumer Packaging and Labelling Regulations

- CPLA

- Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act

- FDA

- Food and Drugs Act

- FDR

- Food and Drug Regulations

- FFVs

- fresh fruits and vegetables

- FFVP

- Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Program

- FFVR

- Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations (or FFV Regulations)

- FSAP

- Food Safety Action Plan

- FSIP

- Food Safety Investigation Program

- HC

- Health Canada

- IM

- Inspection Modernization

- LAR

- Licensing and Arbitration Regulations

- MCAP

- Multi Commodity Activities Program

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PCP

- Prevention Control Plan

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- RCC

- Regulatory Cooperation Council

- RPWs

- registered produce warehouses

- SFCA

- Safe Food for Canadians Act

- TBS

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

1.0 Introduction and Context

1.1 Description

Program Structure

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) regulates fresh fruits and vegetables (FFVs) to verify that fresh produce imported, exported and marketed inter-provincially under Federal legislation is safe, wholesome and graded according to standards, packaged and labelled to avoid fraud or misrepresentation and marketed in an orderly fashion. The average Canadian consumes about 55 kg of vegetables each year, and 39kg of fruit. Canada imported an average of $5.9 billion worth of fruits and vegetables annually from 2008-11, and exported an average of $1.5 billion.Footnote 1

The FFVs industry is, for the most part, an unregistered sector. The sector is not subject to any mandatory registration requirements, although there are approximately 90 registered produce warehouses (RPWs) across Canada, which participate in a voluntary program for permission to grade potatoes, apples and blueberries marketed in interprovincial trade. By contrast, the typical registration function of other CFIA food programs is for the purposes of granting "permission to operate" and for implementation of food safety systems in food establishments.

The Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Program (FFVP) is housed in the Agrifood Division of the Policy and Programs Branch and is internally divided into two sections: safety and quality. In 2011-12, the Program's expenditures represented slightly more than 3.5% of the Agency's overall budget, that is, $27.9 million (and $33.6 million in 2012-13). Historically, oversight of the two sections was provided via two chiefs that reported to a single national manager responsible for all program policy, performance, reporting and implementation. During a recent restructuring, responsibility for the quality (non-food safety) section of the FFV Program was transferred to the National Manager of Processed Products, Maple and Honey Program, involving the transfer of two full-time equivalents (FTEs) at Headquarters. The Operations Branch supports the FFV Program as a whole, coordinating delivery between safety and quality sections and prioritizing tasks required for Program delivery. The Science Branch manages the sampling programs, including all planning, laboratory analysis and reporting, plus targeted surveys.

Table 1 shows FFVP expenditures and budgets for fiscal years 2008-13.

| Expenditures (Including Internal Services) | Budget (Including Internal Services) | Variance | Variance % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 9,278,919 | 9,597,696 | 318,776 | 3.3% |

| 2009-10 | 10,966,417 | 11,177,787 | 211,370 | 1.9% |

| 2010-11 | 10,475,760 | 10,556,263 | 80,503 | 0.8% |

| 2011-12* | 27,908,682 | 29,956,649 | 2,047,968 | 6.8% |

| 2012-13* | 33,584,116 | 35,171,856 | 1,587,740 | 4.5% |

*See Table 2 for breakdown

The way in which the Agency reported FFVP finances changed dramatically in 2011-12 because the Agency realigned its Program Alignment Architecture (PAA), downsizing from eight Programs to five. The breakdown of Program activities is shown in Table 2. The Agency has produced no reports to indicate which activities (see sub-sub activities in Table 2) were added or newly attributed to the FFVP to account for the near tripling of expenditures from 2010-11 to 2011-12. There are also no reports showing the breakdown of budget figures by activity or by any other criteria for the Program as a whole. To determine Program budget figures per activity would require a review of the FFVP financial planning per branch. Each branch manages its own budget and does not participate in any summary exercise to create a single comprehensive budget for all Agency expenditures associated with fresh produce. Expenditures are similarly documented within each branch separately. This gap in accounting and planning is not reflected in any of the recommendations because the FFVP will become part of the Agency's larger food program during the Agency's modernization initiatives over the next few years. However, for planning purposes, it is important for the Agency to ensure that such expenditures are more accurately, consistently and comprehensively tracked. Tables 1 and 2 were created from information developed for the evaluation by the Corporate Management Branch.

| CFIA PAA Sub-Sub Activities | 2011-12 Expenditures (Including Internal Services) |

2012-13 Expenditures (Including Internal Services) |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory and Policy Analysis and Development | 528,549 | 328,161 |

| Science Advice | 2,435,288 | 6,491,253 |

| Communication and Stakeholder Engagement | 764,046 | 582,228 |

| Programs Design, Advice and Training | 4,416,262 | 3,640,397 |

| Inspection / Surveillance | 9,821,545 | 10,551,024 |

| Laboratory Services | 8,028,701 | 7,180,176 |

| Contingency and Preparedness | - | 221 |

| Internal Management | 59,379 | 2,483,857 |

| Export Certification - FS - FFV | 1,488,119 | 1,976,892 |

| International Engagement and Standard Setting | 366,793 | 349,90 |

Total |

27,908,682 | 33,584,115 |

Notes on Tables 1 and 2: A) Actual expenditures by sub-sub activity come from the year-end actual expenditures by sub-sub activity report; B) The allocation of internal services is included pro rata in the actual expenditures by sub-sub activity (ranging from 17-21%), which accounts for the difference in the figures in the Departmental Performance Report; C) The budget for the FFVP specific to the International Collaboration and Technical Agreements (ICTAs) sub-sub activities was allocated on a pro-rata basis according to the fiscal year end sub-sub-activity expenditures in ICTAs; D) Main Estimates of 2011-12 by PAA were restated for this exercise. In 2011-12, the Agency realigned its PAA, downsizing from 8 Programs to 5. During the realignment, the CFIA worked to accurately apportion its Planned Spending to the New Programs. However, while preparing the 2011-12 Departmental Performance Report, it was noticed that authorities did not properly align with actuals. This issue was corrected in the 2013-14 Report on Plans and Priorities. Therefore, Main Estimates of 2011-12 by PAA were restated in this exercise to provide a more accurate basis for evaluation; E) Some of the increase in Science Advice expenditures in 2012-13 is reportedly due to the transfer of approximately 50 CFIA staff members from the Policy and Programs Branch to the Science Branch.

The number of staff working directly in the FFVP is outlined by Branch in Table 3.

Table 3: FFVP Full Time Equivalent Staff 2012-13Footnote 2

| Branch | Section | FTE |

|---|---|---|

| Science Branch | Laboratory | 8.0 |

| Science Branch | Advice | 3.0 |

| Operations Branch | Food Safety inspectors | 17.5 |

| Operations Branch | Market Access inspectors | 26.4 |

| Policy and Programs | Food Safety | 9.9 |

| Policy and Programs | Market Access | 1.0 |

| Total | 65.8 |

Authorities

The following acts and regulations are enforced by the FFVP:

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency Act (CFIAA)

- Canada Agricultural Products Act (CAPA), to be repealed on the coming into force of new regulations under the Safe Food for Canadians Act

- Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act (CPLA)

- Consumer Packaging and Labelling Regulations (CPLR), food related provisions are also intended to be repealed with the making of new regulations under Safe Food for Canadians Act

- Food and Drugs Act (FDA)

- Food and Drug Regulations (FDR)

- Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations (FFVR or FFV Regulations)

- Licensing and Arbitration Regulations (LAR), *possible removal of the LAR is proposed under a Regulatory Cooperation Council Initiative.

The Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) was enacted in November 2012. It will come into force along with the making of new regulations, whose target date is 2015-16. Under the new Act and proposed regulations, commodity-based programs such as the FFVP will cease to exist as distinct programs, as the Agency moves to a risk-based multi-commodity approach to food safety oversight, making prevention a priority across all food commodities and implementing a common inspection approach across all foods. The proposed regulations will have a number of horizontal requirements applicable to all federally regulated food commodities traded inter-provincially and internationally, such as involving licensing, preventive controls, traceability, record-keeping and a review mechanism. Certain commodity specific food safety requirements will be maintained (e.g. regarding slaughter), as will other commodity-specific and consumer-protection provisions (e.g. standards of identity, grades, inspection marks, labelling and packaging). While many of the FFVP functions will continue, this transition will have broad implications for the FFVP sector.

Regulatory Framework

The FFVP has two distinct mission areas, with different histories, cultures, relationships and levels of CFIA experience. These two areas are:

- food quality, related to marketing and market access; and

- food safety

Quality-Marketing-Market Access

The marketing of fresh fruit and vegetables is regulated under the Canada Agricultural Products Act (CAPA) by way of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations (FFV Regulations) and the Licensing and Arbitration Regulations (LAR).

The CAPA regulates the marketing of agricultural products in import, export and interprovincial trade and provides for national standards and grades of agricultural products for their inspection and grading, for the registration of establishments and for standards governing establishments.

The FFV Regulations set out packaging, labelling, non-food safety (grade standards) and food safety requirements for fresh fruits and vegetables marketed in import or interprovincial trade, whether they are supplied fresh to the consumer or for food processing.

The FFV Regulations provide that for the following commodities traded inter-provincially, each load must undergo a CFIA shipping point inspection and be certified as meeting an established grade:

- Apples from British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick or Nova Scotia;

- Potatoes from Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia or Prince Edward Island; and

- Blueberries packaged in containers of 6 litres or less from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick or Prince Edward Island.

Inspection certificates are valid for not more than three days (including Saturdays and holidays). Exceptions for mandatory shipping point inspections are made for establishments that are registered with the CFIA in the Registered Produce Warehouse Program. Establishments who are part of this program are subject to regular inspections to demonstrate the continued ability to pack product to quality standards, as an exception to the general requirement for inspection for each load.

The Licensing and Arbitration Regulations were designed to ensure fair and ethical trading practices in the international and inter-provincial trade of fresh fruits and vegetables. The Regulations require Canadian importers (with more than $230,000 in annual sales) to be licensed with the CFIA and/or be a member of the Dispute Resolution Corporation (DRC). A CFIA license or membership in the DRC provides a mechanism for dispute resolution of any quality or payment issues in produce transactions. There are approximately 115 license holders and 800 DRC members. Licenses are issued by the CFIA's Destination Inspection Service (DIS). The DIS is an impartial service provided by the CFIA to support the resolution of disputes related to FFV quality. Inspections offered by the CFIA deal with the following issues: defects, witnessing of product disposal and weight, size, or actual count. There are fees associated with DIS services and the CFIA is moving towards full cost-recovery. The DIS was created in 2007 from functions that were performed up to then by the FFVP.

There are programs within the FFVP that were established to ease the grade inspection burden. As referenced above, the Registered Produce Warehouse Program (RPWP) allows products to move between provinces without the need for mandatory quality inspections on each outbound load. The regulatory basis for this Program is contained in Part X of the FFV Regulations, which allows any establishment that prepares commodities for which the Regulations have established gradesFootnote 3 to become registered. However, in practice, only those establishments preparing apples and potatoes have registered as they are the commodities for which an inspection is mandatory. The purpose of the Program is two-fold: to provide the industry with flexibility to ship produce without waiting for an inspector (by demonstrating capacity and compliance with grading and grade declarations); and to reduce the CFIA's resource requirements by reducing the number of shipping point inspections. There are 90 potato and apple establishments in this program.

The FFVP's Canadian Partners in Quality (C-PIQ) Program allows potato producers to enter into an agreement with the CFIA requiring them to maintain performance standards which allows them to complete their own export certificates for loads of potatoes being shipped to the U.S. The Agency conducts audits and reviews company quality assurance manuals and records to verify compliance. There are approximately 15 establishments in the C-PIQ Program. This program is not supported through regulations but instead uses legally binding participation agreements between the CFIA and potato establishments.

Safety

A general requirement for safe food is found in the FFV Regulations under the CAPA. Subsection 3 (1) of the Regulations states that "no person shall market produce in import, export or interprovincial trade as food unless it . . ." is safe to consume. In addition, the Regulations set out in detail various banned contaminants. The delivery of the safety aspects of the CFIA's FFVP is broken into two basic components: (1) sampling conducted under the National Microbiological Monitoring Program (NMMP), the National Chemical Residue Monitoring Program (NCRMP) or the Food Safety Action Plan (FSAP); and, (2) reactive investigations, including recalls, trace backs and directed sampling.

The CFIA uses two broad strategies to monitor for the presence of various hazards in foods including FFVs. These two strategies include regular monitoring programs such as the NMMP and the NCRMP as well as targeted surveys and studies. The NMMP and NCRMP are monitoring programs that apply to a wide variety of domestic and imported food products (not exclusively FFVs). The NMMP monitors the level of microbiological contamination in the food supply, testing for a variety of high-risk pathogens including E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella and Shigella. The NCRMP tests for the occurrence of chemical residues, food additives and toxic metals. Both monitoring programs are intended to identify trends, risks and areas for follow-up actions to help minimize potential health risks for consumers. Based on multiple factors such as consumption by Canadians, compliance history and considerations regarding vulnerable sub-populations, the level of monitoring is identified and adjusted as needed. In addition to regular monitoring activities, additional testing is conducted under the FSAP in areas of highest or emerging concerns. Under the FSAP enhanced surveillance program, information is collected through targeted surveys on chemical and microbial hazards as well as allergens. Currently these surveys include the testing of identified priorities (FFV examples include cantaloupes, tomatoes, leafy greens and fresh herbs) for various microbial hazards. Surveys investigating the levels of allergens (sulfites in various FFV commodities such as lychees and grapes) have also been completed). Studies on pesticide levels in FFV traded intra-provincially have also been completed.

The investigative component of the FFVP does not include prescriptive requirements such as licensing (outside LAR requirements), on-site inspections, or the development and implementation of preventive control plans, as no preventive food safety regulations currently exist for this sector. As a result, current oversight is primarily responsive to food recalls and emergency issues, such as responses to outbreaks of food-borne illnesses, complaints from the public and evidence of microbiological contamination from the NMMP which may require directed sampling as part of an investigation into the origin of the contamination.

It is interesting to note that despite the absence of formal food safety requirements and protocols through legislation or CFIA policy, a voluntary industry-led program has emerged called CanadaGAP. CanadaGAP is a food safety program for companies that produce, pack and store fruits and vegetables, designed to help implement effective food safety procedures within fresh produce operationsFootnote 4. This industry-run safety program was developed with the help of funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). The industry estimates that possibly as many as 70% of FFV producers in Canada are members of this program. This includes those selling to large retailers who are said to be increasingly insisting on the implementation of effective risk mitigating processes and strategies in this sector.

A full profile and description of these two functions, primarily compiled by FFVP management for the purposes of this study, is provided in Annex A. This information will be drawn upon in addressing the issues in Section 3.

Summary Program Context

The FFVP has a long standing history, oriented to market access, quality and, sometimes, to manage the availability and supply of certain commodities. This began as far back as the 1890s for grade standards for apples, and more broadly across commodities in the 1930s, all to assist trade through the use of a common language. See the "Service" History with Sector discussion in Section 3.1.4 below. The regional presence to the sector in these areas remains strong. In this context, the CFIA is seen by industry as a key partner in helping them market their products and secure access to other markets.

Inspection Modernization (IM) and the new Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) represent transformative initiatives for CFIA which place the emphasis on food safety. With respect to the oversight of FFV products, stronger food safety rules under the new Act will mark an expansion of the regulatory scope of the Program which had previously been focused on quality and market access.

1.2 Evaluation Context (Scope and Objectives)

The need for an internal evaluation of the FFVP was identified in the CFIA's Evaluation Plan (2012-2017), which was reviewed by the Evaluation Committee and approved by the CFIA President in June 2012 (confirmed in the Evaluation Plan 2013). The timing of this evaluation allows the CFIA to conform to requirements of the Policy on Evaluation for evaluation coverage of all direct program spending, and to provide observations about the FFVP as changes in program design and regulations are being made.

The FFVP falls under the CFIA's PAA Program Activity 1, the Food Safety Program, which is linked to the overall strategic outcome of having a safe and accessible food supply and plant and animal resource base.

This evaluation examines the FFVP's relevance and performance during the period from 2008 to 2013. However, it also examines the implications of the past and present with regard to future directions, including current modernization initiatives.

For the purposes of this evaluation, the "Program" under evaluation includes all related areas across the Agency, including those in Policy and Programs, Operations and Science Branches. Relevant FFVP activities undertaken by external programs that interface with the FFVP such as the Plant Protection Program, Destination Inspection Services and the Office of Food Safety and Recall were also taken into consideration. This evaluation was initiated in March, 2013. Its data collection was completed in November, and its reporting in December.

Evaluation Issues

As required by the TBS Policy on Evaluation (2009), the main aim of the CFIA evaluation of the FFVP was to address the five core evaluation issues outlined below. In addition, the evaluation team was asked by its Advisory Committee to look at examples of other program areas that transitioned from a quality to a safety focus and how other governments regulate FFV, all to share lessons learned. See Methodology Section for details.

Relevance

Issue #1 Continued Need for Program

Assessment of the extent to which FFVP policies, processes and relationships continue to address a demonstrable need and are responsive to the needs of Canadians.

Issue #2 Alignment with Government Priorities

Assessment of the linkages between FFVP objectives and (i) federal government priorities and (ii) Agency strategic outcomes.

Issue #3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Assessment of the roles and responsibilities for the federal government in delivering the FFVP.

Performance (effectiveness, efficiency, and economy)

Issue #4 Achievement of Expected Outcomes

Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (including immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes) with reference to performance expectations and program reach, as well as program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

Issue #5 Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

2.0 Methodology

2.1 Description

A realistic contribution analysis approachFootnote 5 was used for this evaluation to respond to the five core issues of the evaluation. This approach provided a rigorous process for validating and refining the understanding of the results logic and the factors affecting performance. (See Annex C for further details on the approach.) The Evaluation Directorate worked with the FFVP to further identify areas of risk to the Program and their impacts. Multiple lines of evidence were used to provide a better understanding of the Program. These multiple lines of evidence included a needs review, instruments review, literature review related to instruments and initiatives, international comparative case analyses, file review evidence analysis and interviews to validate, extend and address issues. Triangulation of data was done by issue.Footnote 6 Documents reviewed are included as Annex G. An Advisory Committee was established for the Evaluation with senior management representation from the Science Branch, Operations Branch, Policy and Programs Branch and Public Affairs Branch. In addition, the Committee included the Director of Evaluation from Transport Canada to provide an outside perspective.Footnote 7 The Committee reviewed and provided advice on the Evaluation Framework, the preliminary findings and draft report.

| Interviewees* | Consultations** | |

|---|---|---|

| CFIA Staff | 27 | 17 |

| Other Federal Department/Agency Representatives | 7 | 3 |

| Provincial Government Representatives | 1 | |

| International Government Representatives | 2 | 2 |

| Industry Association Representatives | 10 | |

Total |

47 | 22 |

footnotes: *Interviews followed the protocol set out in the interview guides, in Annex E. Note that in several cases multiple call-backs were conducted with interviewees.

**Consultations were conducted by e-correspondence, meetings and phone calls and aimed at developing and testing the evaluators' understanding of key issues related to the FFVP and the FFV sector. Examples include consultations on past, present and proposed processes as applied, compared and contrasted for FFVs vs other groups, and it included attempts to clarify performance and resource usage information. The numbers in this category exclude the call-backs to respondents interviewed in the previous column. Note that while the perspectives of major stakeholders were considered key, non-stakeholders were included where appropriate.

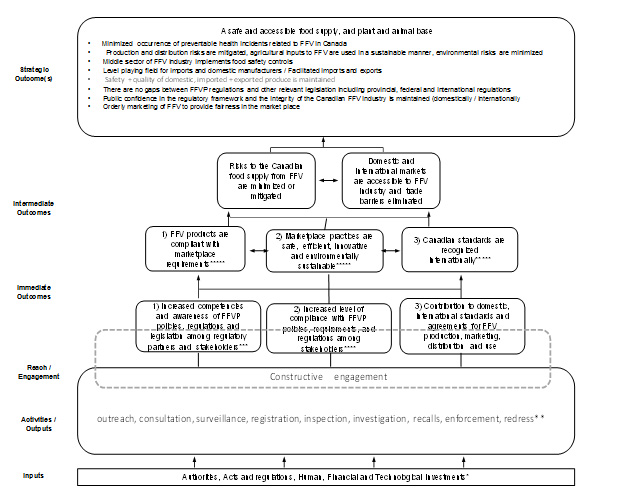

A performance measurement strategy did not exist for the FFVPFootnote 8. As a result, a logic model for the Program was produced by the evaluation team as part of the evaluation planning, and was subsequently validated through interviews and consultations, including with program staff. A systems performance framework was developed, identifying key factors deemed to be critical to the successful delivery of the FFVP. An FFV Evaluation Framework was developed at the evaluation's outset and included a list of the key sectors involved in the achievement of the FFVP missions. These components represent a theory of the Program and the relations between them were tested as part of data collection and analysis. This information should also serve to inform the development of the integrated food program, as it identifies key FFVP-related outcomes and activities. Specific FFVP elements can be considered in conjunction with the generic model to determine which are specific to this sector. See Section 3.1.4 and Annex B for the logic model.

2.2 Limitations

The circumstances in which this evaluation was conducted created special limitations:

| Limitations | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|

| i. High uncertainty going forward – The Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) and the Inspection Modernization (IM) initiative together represent the largest transformation in CFIA history. The full extent and implications for these changes in the FFV sector are as yet unknown and continue to evolve, though it is clear that under the new model, the FFVP will cease to exist in its current form. | Focus on past and present practice with a view to the future. Questions about the Agency's modernization initiative and the future needs and challenges for the FFVP were included in the evaluation lines of inquiry (See interview guides and evaluation matrix in Annex E and Annex F respectively). |

| ii. Limited information from the past (and present) – Due to the nature of the FFVP (no history of establishment-based or safety-oriented inspection, limited product testing), there is limited information on the sector regarding producers, produce safety risks, compliance rates, etc. Without such data it is not possible to make definitive conclusions on the Program's influence on the sector. | The study drew on available evidence from testing and special studies, as well as literature and documents to systematically review the results and key factors affecting the systems results of the FFVP. A review of the experience in the U.S. also provided valuable related data. |

| iii. Relevant studies - Accessing relevant, timely program level studies on FFV safety has been challenging given the lack of a systematic approach to safety and the lack of sector information noted above and below in part vi (i.e. there has been no systematic prevention program to date, hence no baseline information). | See the above. Plus extra time was taken to generate and produce information. |

| iv. Data challenges - Accessing program performance measurement information in current databases (e.g. Multi Commodity Activities Program) has been challenging.Footnote 9 The current system is not set up to provide meaningful performance information on key Program functions such as the extent of inspection and testing, the levels of compliance and breakdowns by sub-sector or region, etc. | See the above. Special data runs were required and different groups were consulted to attempt to cross-validate data. |

| v. Selection/sampling bias - Since CFIA staff and in some cases interviewees provided the names of the stakeholders interviewed for this evaluation, this might have resulted in a possible selection or sampling bias (i.e. a systematic error due to a non-random sample of a population, causing some members of the population to be less likely to be included than others and resulting in a sample in which all population members are not equally balanced or objectively represented). | The impacts of a potential selection or sampling bias were minimized by framing interview questions and prompts in a manner that encouraged interviewees to provide verifiable examples and supporting documents in relation to their answers, wherever applicable. This is also mitigated by triangulating multiple lines of evidence (e.g. reviewing internal and external documents to identify and assess any concerns or opinions that might not have been reported or shared by internal stakeholders). |

| vi. Nature of the FFV marketplace – Difficulties are encountered when attempting to demonstrate results and their impacts due to the fact that the FFV marketplace is a highly complex environment with many factors and interactions. It was difficult to attribute results to the FFVP with so many different players involved in the results chains. (See Reach and Results chart in Annex B, Figure B-3.) Knowledge of the sector in its totality is difficult. Another constraint was the difficulty to verify the links / traceability between FFV and foodborne illnesses due to limits in data. (partially as a result of the complex marketplace and partially as a result of current systems approaches - see above). | The explicit review of estimates, along with the repeated consultation of key informants was used to estimate value where data was not readily available. |

Some of the limitations noted above presented significant challenges to being able to conduct a conventional evaluation. The basic strategy to address the data quality problem included a major review of key mechanisms and the experiences of other groups with such mechanisms. The results of the review were used to complement the limited and sometimes non-existent experience of the FFVP in areas like establishment-based inspections, risk-based prevention activities, and outcome-based standards. This approach was designed to leverage as many data sources as possible. Interviews were conducted with a variety of stakeholders: CFIA staff, industry players, other government departments and international groups.

3.0 Key Findings

3.1 Evaluation Issues/Questions

3.1.1 Relevance: Continued Need for Program

Assessment of the extent to which FFVP policies, processes and relationships continue to address a demonstrable need and are responsive to the needs of Canadians.

Findings Summary:

Systematic risk assessments worldwide and key informant interviews suggest that there is a strong need for a regulatory program devoted to food safety in the FFV sector. International agreements related to specific commodities continue to require grading and other quality related support. This suggests a continued need for some form of market access.

There is a need for the FFVP to continue in some form, whether as a distinct program approach or as part of an integrated approach envisaged under the Safe Food for Canadians Act.

The Issues Analysis Summary, issued in April 2013 by the CFIA's Food Safety Division, suggests that there is a 'large body of evidence', both domestically and internationally, relating to increased incidents of FFV-related food-borne illnesses. The report concludes that fresh fruits and vegetables "are increasingly becoming a food safety concern."

From a food safety perspective, the health risks inherent to this sector are very significant. According to recent U.S. studies, food-borne illness outbreaks for produce are reportedly comparable in number to those for meat products. Although a number of differences characterize these two sectors, including regulatory and export requirements, it is worth noting that the Agency spends significantly more on regulatory oversight for the meat sector than it does for the FFV sector. In 2011-12, the Agency allocated 35.2% of its budget to Meat and Poultry, and 3.8% to Fresh Fruits and Vegetables.

A study conducted in 2013 by the U.S. Centre for Disease Control (CDC) calculated that for 4,589 foodborne illness outbreaks with single etiology between 1998 and 2008, causing 120,321 illnesses, it was produce commodities that accounted for 46% of these illnesses while meat and poultry accounted for 22%Footnote 10.

An alternate view was provided in a 2013 paper by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (Outbreak Alert! 2001-2010 A review of Foodborne Illness in America). This paper agreed with the basic numbers of the CDC report "which put the spotlight on produce as causing the most cases of foodborne illness", but it arrived at different conclusions. The paper analysed the outbreaks by volume of product consumed, which identified seafood as the greatest cause of disease, followed by poultryFootnote 11. Both reports take great pains to list many caveats and assumptions, but both recognized produce as a major cause of food-borne illness outbreaks.

Recent assessments suggest that FFV risks are heightened, or greater than previously thought, due to:

- Consumer habits (fresh, but conveniently packaged food);

- General lack of a "kill step" as products are often eaten raw;

- Large batches of fresh fruits and vegetables transported over long distances;

- Globalization of produce value chains and increases in both the variety and quality of products produced has dramatically increased the number of potential contamination points;

- Increases in imports from developing countries with various safety systems;

- Increased scientific knowledge and experience regarding microbial risks in fresh produce have illustrated the risks; and,;

- Increased interest by key trading partners (U.S., EU, Australia, New Zealand) and recognition that a reactive system is not acceptable.Footnote 12

Given the findings from both internal and external reviews of the sector, it is clear that there is an ongoing need for some form of programming for this sector in order to satisfy food safety objectives.

Looking ahead, the Agency's modernization initiatives demonstrate a continued focus on food safety and on building a more consistent and comprehensive framework across commodities. These efforts are intended to strengthen food safety, including for the FFV sector. From a stakeholder perspective, major associations support, both in words and in actions, the CFIA's shift in orientation more towards safety – further supporting the perceived need for a program covering this sector. This is evidenced by industry led quality and safety assurance programs that have emerged in Canada, the most prominent one being CanadaGAP, specifically for the FFV sector.

From a quality-marketing-market access perspective, given U.S. certification and interprovincial inspection requirements, there appears to be a continued need for this aspect of programming. The CFIA's role in certifying that products meet quality standards (grades) for the FFVP sector has dominated the relationship between the CFIA and industry. While the CFIA's role is traditionally one of regulator for most other commodities, it is generally considered to be providing a necessary service by FFV producers who rely on it. The current need for the service stems from regulatory requirements driven by trade and market access objectives. Its activities largely involve certifying grades to demonstrate adherence to target product specifications relating to product characteristics, including the purpose of avoiding fraud, with rare or no links to food safety.

Pursuant to subsection 2.2(2) of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations, the Minister may issue a Ministerial Exemption (ME) to exempt a product from regulatory labelling and/or packaging requirements in order to prevent or alleviate a shortage of product in Canada. The intent is to reduce shortages while maintaining overall supply levels at a controlled level. This is intended to maintain relative price stability which in turn serves the commercial interests of Canadian producers and consumers. While only a handful of interviewees commented on MEs, they consistently perceived them positively as providing critical support to manage the availability and supply of certain commodities. The number of MEs varies from 10,000 to 20,000 loads of FFVs per year, essentially allowing bulk product shipments to address shortages for the purpose of managing prices.

A regulatory requirement exists for apples, potatoes and blueberries, destined for interprovincial trade, to be inspected to ensure they meet the established grade. Subsection 29 (2) allows for a release permit (referred to as a "Y" release) to be issued by inspectors if they do not have time to inspect the load within the prescribed time (24 hours if an inspector is in the area or 48 if not). Over a three year period from 2010 to 2013, the CFIA issued 2,648 "Y" releases and conducted 646 inspections. These results illustrate that the Agency had capacity to inspect these products only 25% of the time. As a result, the core quality-based inspection requirement was not met 75% of the time. In other words, these products are shipped and traded without an inspection most of the time. The level of 'exemptions' from inspection through "Y" releases raises questions about the need for such inspections.

The need for the Registered Product Warehouses Program and for the Canadian Partners in Quality (C-PIQ) Program is similarly linked exclusively to supporting industry's trade needs. The former allows products to move between provinces without the need for mandatory quality inspections on each outbound load, which provides the industry with the flexibility to ship produce without waiting for an inspector, and reduces the CFIA's resource requirements by reducing the number of shipping point inspections. The C-PIQ Program allows potato producers to enter into an agreement with the CFIA requiring them to maintain performance standards, which allows them to complete their own export certificates for loads of potatoes being shipped to the U.S.

These programs represent examples of how quality requirements are satisfied through alternative means that have received support from industry. These illustrate that even where regulatory requirements exist relating to issues of quality, the role of the CFIA may vary. Industry has expressed the need for such services, but no evidence was found to indicate that government has to be the one that provides them.

Quality related services have been successfully disengaged from the Agency and taken up by the private sector for such commodities as seeds, beef and fertilizer. The experiences from these changes in responsibility provide rich lessons from which the Agency can draw during any consideration of transitioning FFV grading services to the FFV sector. These experiences also point to challenge areas. The following are some of the key contextual factors that appear to have been important to the transitions:

- Relative stability in terms of grading practices and low controversy in terms of grade levels were important conditions;

- A low number of key players kept the negotiations straight forward;

- Comparatively high price increases (cost recovery by the CFIA) just prior to transition helped to incentivize the industry to take over grading;

- Financial assistance was provided by AAFC to help industry make the transition;

- Trained government graders were recruited and used in the private take-over;

- Resistance was strongest from small growers who preferred the simpler (and at one time free) Government of Canada grading services, and;

- Respected industry players were key to leading the transition.

The extent to which these success factors are present has not been fully explored in this evaluation.

3.1.2 Relevance: Alignment with Government Priorities

Assessment of the linkages between FFVP objectives and (i) federal government priorities and (ii) Agency strategic outcomes.

Findings Summary:

A review of documents shows that the FFVP's food safety objectives clearly align with federal government priorities, as set out in the Safe Food for Canadians Act, as well as with the Inspection Modernization initiative and the Agency's strategic outcomes. The support for market access is explicit in current regulations. Once in force, the Safe Food for Canadians Act will provide authorities for regulations to support trade. Support for market access is indirectly aligned with the Agency's current strategic outcomes.

FFVP Objectives vs. Federal Government Priorities

Food safety and market access, the two key objectives of the FFVP, have been long-standing government priorities. They were once again recognized in the 2013 Speech from the Throne (delivered on October 16, 2013) as priorities for the Canadian Government going forward. The recently passed Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) was also recognized as "a significant milestone in strengthening Canada's world-class food safety system". In addition, trade and market access priorities are also recognised in the 2013 Speech from the Throne, further re-enforcing the linkage between the objectives of the FFVP and the current government priorities.

The Safe Food for Canadians Act and the proposed regulations that are under development are expected to provide a clear foundation for the food safety objectives relating to FFV. With regard to the Government and especially the Agency's role with respect to quality, marketing and market access for FFV products, there is an overall commitment found in the CFIA Act's preamble, which states that "the Government of Canada wishes to promote trade and commerce". Under the authority of the Canadian Agriculture Products Act, the FFV Regulations outline requirements for product grades and other marketing criteria. The regulations are referred to as Regulations Respecting the Grading, Packing and Marking of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables. They include "Schedules" that outline grade and container size requirements. The Agency is expected to import the existing FFV Regulations under the regulatory framework supporting the SFCA, so they will continue to be in force after the implementation of the SFCA. The plan to continue these regulatory requirements supports the view that this objective and these provisions remain necessary and relevant at this time, though, as noted above, there is some uncertainty regarding the fundamental need that they serve. A number of interviewees questioned the continued need for the federal government to have a role in trade support for the FFV sector.

FFVP Objectives vs. Agency Strategic Outcomes

Analysis of the FFVP's objectives vs. the Agency's strategic outcomes shows that the Program is generally consistent with the CFIA's strategic outcome: A safe and accessible food supply and plant and animal resource baseFootnote 13. Clearly, the food safety aspects of the Program align directly with this strategic outcome, but the FFVP's quality and market access activities are more indirectly linked to it.

The Program's quality and grading support work addresses this strategic outcome if 'accessible' is interpreted as including access to foreign markets. The results statement for the CFIA's International Collaboration and Technical Agreements Program states: "international markets are accessible to Canadian food, animals, plants and their products."Footnote 14 The extent to which the CFIA should go to encourage accessibility is not elaborated on. The prescribed indicator "number of unjustified non-tariff barriers resolved" does not necessarily suggest an active role in export certifications. However, it should be noted that in the Agency's 2014-15 Report on Plans and Priorities, under the "Raison d'être" heading, it identifies "contribute to market access for Canada's food, plants, and animals" as the fifth of five reasons for the delivery of inspections and other services. While fulfilling trade objectives for this sector is clearly relevant to the Agency's mandate and strategic outcomes, program documents, interviews and performance data raised uncertainty regarding whether existing regulations and programming best align with current objectives and priorities.

In short, the Agency's own outcome statements, particularly those in the SFCA and related consultation documents, focus on food safety. However, there are currently more inspectors at the CFIA working on quality and market access for FFV than on FFV safety.

The existing FFVP is out of alignment with a number of key elements or principles being implemented under the CFIA's modernization agenda. Notably:

- A risk-based preventive approach: According to CFIA internal documentsFootnote 15 and interviews, there is a lack of preventive food safety programming specific to fresh produce in Canada - except for those run by industry;

- Outcome-based standards: A review of current practice suggests that there are currently no safety related outcome-based standards for fresh produce in place. According to a recent CFIA consultation document, outcome-based approaches to standards emphasize what must be achieved, not necessarily how it must be achievedFootnote 16. While the Agency is currently developing such standards, there are a number of challenges, such as the requirement for substantial guidance documentation (also under development). See Annex D for an analysis of international experience in the development of outcome-based standards. This is also discussed in Section 3.1.4.

- Comprehensive licensing: There is currently only 'voluntary' registrations for market access purposes in place in this sector,Footnote 17; and,

- Standardized establishment-based inspections. Such inspections have never been done by CFIA for the FFV sector, outside of a small pilot project in 2010-12.

The extent to which key elements of the new initiatives can and will be effectively implemented by the Agency with respect to the FFV sector is daunting given its past orientation, limited capacity and its service relationship with the sector. (See performance observations in Sections 3.1.4 and 3.1.5) Actions underway as part of the broader Agency transformation process are intended to address many of these implementation challenges. This includes industry and stakeholder consultation on the development of stronger food safety rules (including outcome–based standards and licensing requirements), the delivery of improved training to inspectors to align with the new inspection model, the implementation of a Statement of Rights and Service to better articulate roles and responsibilities for industry and consumers and guidance and compliance promotion materials (including model systems) for regulated parties.

3.1.3 Relevance: Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Assessment of the roles and responsibilities for the federal government in delivering the FFVP.

Findings Summary:

Up to now, CFIA's main FFV safety role, responsibilities and activities have been oriented to selective monitoring, reaction and remediation rather than being driven by establishment-based risk analysis and oversight. Furthermore, the CFIA's overall main active FFV role to date for the FFV sector, as shown by delivery activities and resource use, has been to support market access.

Recent FSAP test results, CFIA risk assessments and key interviews point to the importance of emerging CFIA roles, such as those related to microbial (pathogens) threats (see the Science Branch's 2013 risk assessmentFootnote 18).

As noted above in Section 3.1.2, the increasing linking of FFVP with food safety roles and responsibilities is demonstrated by recent legislative initiatives and the transformational agenda in the Safe Food for Canadians Action Plan consultation documentFootnote 19. At the same time, the Agency has signalled its intention to integrate the provisions relating to quality and market access into the proposed regulations supporting the SFCA. This suggests an intention to maintain a dual focus on quality and safety for the FFV sector.

Reviews are mixed with respect to the CFIA's role in quality and market access. The role has been seen by some as posing an unnecessary burden on industry. Some industry representatives questioned whether it was necessary to subject them to CFIA verifications of their grade in order for them to sell their product in certain markets.

The CFIA's increasing emphasis on food safety programming for the FFV sector is nascent and unclear in some areas at the time of this evaluation (e.g. the full extent of the CFIA's authorities to inspect and regulate on the farm have been inconsistently interpreted by CFIA staff). Given the intention to maintain support for the quality objectives while apparently significantly expanding the safety objectives for this sector, there will be a strong need for additional resources to effectively satisfy both types of objectives. The current level of coverage for food safety is recognized as insufficient in CFIA planning documents and by all the CFIA managers who were consultedFootnote 20.

3.1.4 Performance: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (including immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes) with reference to performance expectations and program reach, as well as program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

Findings Summary:

CFIA activities for produce safety are reactive and focus on limited national sampling and testing programs for hazards. As a result, there is insufficient evidence to conclusively state to what degree FFV products in Canada are safe. Evidence suggests that industry requirements and private sector programs play a stronger role in influencing FFV safety than existing CFIA program activities. Contributing to this is the absence of a comprehensive CFIA FFV food safety program, including preventive food safety regulations and extensive sampling and testing. The FFVP quality and market access activities have successfully supported the regulatory requirement and the sector's needs, though some concerns have been raised regarding the Agency's resource limitations. Concerns have also been raised regarding the sector's and the Agency's preparedness for changes planned under the SFCA.

The provision of grading and export services is discussed below.

The CFIA's Performance Measurement Framework presents the FFVP's expected results in terms of compliance to regulations (as is standard for most of the Agency's outcomes):

- Federally registered fresh fruits and vegetable establishments meet federal regulations, and

- Fresh fruit and vegetable products for domestic consumption meet federal regulations.

Regarding the first expected result, the only registered FFV establishments are in the Registered Produce Warehouse Program (RPWP), focussed on quality and market access. Quality and market access performance issues are discussed in the second part of this Section. The second expected result primarily relates to food safety, and is discussed in the first part of this section below.

Program documents provide a bit more detail on expected outcomes. The FFVP's Program Basics document states that intended outcomes are to ensure that fresh fruits, vegetables exported, imported or marketed inter-provincially comply with federal regulations, are graded for economically significant factors, and are packaged, labelled and traded to avoid fraud. An additional objective is to facilitate access to international markets by providing export certification to meet the import requirements of other countriesFootnote 21. As discussed in Section 1, the regulatory requirements are primarily found in the FFV Regulations. Regarding food safety, it essentially states that no person shall sell food that is not safe to consume.

As noted in section 3.1.1, three quarters of the produce subject to interprovincial certification is currently being shipped without a physical inspection, under a "Y" release. This suggests that CFIA physical inspection has not been a significant factor in inter-provincial trade. While the scope of this evaluation did not focus on the detailed requirements of quality inspections, interviews and the review of documents suggest that current C-PIQ and RPW processes have imposed some undue burden in the eyes of some regulated parties.Footnote 22

Safety

A study published in 2013 in the Journal of Food Protection, highlighted that foodborne disease outbreaks associated with fresh fruits and vegetables have been increasing in occurrence worldwide. Some recent high profile examples include over 11,000 cases of Norovirus related to strawberries in Germany and China in 2012 and 147 illnesses and 33 deaths related to Listeria contamination in cantaloupes in the United States (2011).Footnote 23 The global context is relevant to domestic safety, given that Canada is a net importer of fresh fruits and vegetables, with an estimated value of $5.9 billion annually. Domestic consumption of imported products is particularly prominent in winter months, contributing to the import of 86% of the fruit and 41% of the vegetables consumed in 2000.Footnote 24

In Canada, 27 produce-related outbreaks, resulting in over 1,500 cases of illness, have occurred from 2001 to 2009. At the federal level, between 2002 and 2011, the CFIA conducted 57 recalls of fresh fruits and vegetables. Of these, 12 were class I recalls indicating a high risk of serious health problems; 32 were class II recalls indicating that consumption can lead to short-term non-life-threatening health problems.

While available data suggests that Canadians experience relatively low levels of food-borne illness outbreaks, analysts have pointed out that Canada's food safety system is reactive, lags behind other countries, and investment is needed to ensure it can adequately protect Canadians, as stated in a 2013 article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal by Richard Holley.Footnote 25 According to this study, foodborne illness surveillance is needed to ensure safety from gastrointestinal infections caused by bacteria such as toxigenic E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter and Listeria (all prevalent in the FFV sector). Without a more rigorous surveillance system such as those used in the United States, Australia / New Zealand and Europe,Footnote 26 there is a possibility that Canadian estimates are not as accurate as other developed countries and that Canadians are not as relatively 'safe' as they might think.

While reported product test results are consistently over the Agency's 95% target for compliance with the regulations, there are significant limitations to the coverage of this generalized reportingFootnote 27 and key interviews and profile documents suggest that the sampling is not generally representative of the sector or the risks.

Under the NMMP, CFIA inspectors sample produce based on an annual plan. The sampling is random but follows the planned selection of product type, based on those at higher risk of contamination. However, the sampling plans are not generally based on statistical analysis, but rather on the available operational capacity to obtain and ship samples to the labs and the labs' capacity and capability. Over the past five years, the collection of samples has ranged from 76-89% of what was planned, as shown in Table 6 below. The Agency's Performance Measurement Framework has a target of 100% for "percentage of fresh fruits and vegetable samples inspected versus the number planned".

Table 6: NMMP Samples 2008-13Footnote 28

| Fiscal Year | NMMP Samples Planned | NMMP Samples Taken | % Delivered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 690 | 524 | 75.9 |

| 2009-10 | 1,166 | 1,038 | 89.0 |

| 2010-11 | 1,282 | 1,069 | 83.4 |

| 2011-12 | 1,312 | 1,025 | 78.1 |

| 2012-13 | 1,175 | 1,022 | 87.0 |

Samples taken include monitoring and baseline studies. Compliance percentages are not available for the above table.

Compliance rates for the NMMP were not available for the years prior to 2011. For 2011-12, they were 99.2% for vegetables and 99.5% for fruit, which were described as fairly typical rates. The figures for 2012-13 were not available.

Under the NCRMP fresh produce samples are assessed for pesticide residues as well as heavy metals, based on maximum residue limits (MRLs) set by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). Exceeding an MRL is a violation of Canadian regulatory requirements that triggers Program and Operations follow up; however, it is not generally regarded as an immediate health risk as the danger is due to exposure over time. Chemical residue testing of FFVs is more extensive than sampling for microbial hazards. Shipments are selected randomly, samples are collected throughout the year, and the number of samples planned is proportional to the importance of the commodity in the diet, taking into consideration the origin of the food and the volume of imports. As such, the sample numbers are statistically representative of the commodities, but not of the countries of origin.Footnote 29

The NCRMP under-delivered on its sampling against annual plans and to a greater extent than the NMMP, with delivery rates ranging between 59.6% and 81.5% as shown in Table 7 below. It is also worth noting that while the highest performance was in 2012-13, at 81.5%, the level of planned sampling for that year was significantly lower (by more than 30%) compared to previous years.

| Fiscal Year | NMMP Samples Planned | NMMP Samples Taken | % Delivered | % Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 8,559 | 6,240 | 72.9 | 97 |

| 2009-10 | 8,268 | 6,323 | 76.5 | 97 |

| 2010-11 | 8,564 | 5,107 | 59.6 | 97 |

| 2011-12 | 8,635 | 5,829 | 67.5 | 96 |

| 2012-13 | 6,014 | 4,904 | 81.5 | 97 |

Note that the source for the compliance percentage is CFIA's DPR. Compliance was not calculated the same way in each fiscal year.

For 2011-12 and 2012-13 imported and domestic FFV compliance was reported separately, their compliance percentages were averaged for this table

As discussed in previous sections, there are concerns regarding the level of sampling. These concerns were confirmed by interviews with key CFIA Science and Program staff and relate primarily to the fact that the low number of samples taken in the NMMP is not representative enough to provide any early warning of a food safety issue. Inspection Modernization plans for FFVs focus on establishment-based safety inspection, rather than only sampling at warehouses, packing plants and retail outlets. In a 2010 article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Richard Holley suggested that because pathogens occur with low frequency, the statistical power of product sampling is inadequate to provide confidence in the overall safety of foods subject to testing.Footnote 30 Arguably, this supports the contention that industry run proactive systems reviewed by a regulatory body may be superior to a product sampling regime – especially one which is already struggling in terms of representativeness.

The problem with moving to a proactive systems based approach is that there is currently limited knowledge about some of the higher risk areas – such as establishments that grow, and in many cases package, produce. There is no history of inspection of produce establishments, let alone sampling. This represents an unknown set of food safety risks. The FFVP has noted that if implementing food safety measures to prevent the introduction of known or reasonably foreseeable biological hazards is the objective, then consideration must be given to the most common sources of contamination of fresh produce - the on-farm production or growing practices for fruits and vegetables, and extending into on-farm and post-farm practices of harvesting, packing, holding, handling, preparing, processing and distributing of fresh produce commodities of high risk – in order to bring improved food safety controls further upstream from the retail marketplace. (See Annex A.)

A pilot project was conducted from 2010 to 2012 with the aim of inspecting 30 establishments that packaged and re-packaged fresh leafy vegetables, green onions and/or herbs in the four geographic areas of the country (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario and Western). Only 17 of the establishments were inspected, for reasons outlined below. While the pilot could not be fully implemented, it was successful in identifying institutional barriers to produce establishment inspection. A key challenge identified was inspector capacity and support. While guidance material was developed to support the pilot, this was a completely new activity for many inspectors. Some of the inspectors who participated in the pilot considered the type of work to be the responsibility of inspectors at a higher pay level. In addition, some inspectors and their managers were not comfortable taking on a food safety inspection role because their experience and prior training had been limited to assessing quality. Inspectors also noted challenges associated with their lack of familiarity with the establishments and their business and operational scope. The draft Establishment Inspection Pilot Project report explained that the move to establishment-based inspection was a major change for inspectors that would require significant additional communication, engagement and training. The study further noted a lack of performance information on compliance at both an output and outcome level. It is not evident that any improvement has been made in this situation since the draft report was written in 2012.

The SFCA and attendant modernization agenda commit the Agency to require such establishments to obtain licenses, starting in 2015. The licenses would require a food safety system, referred to as a "preventive control plan" by the CFIA, such as a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system. Until now, the Agency's move in this direction has been limited to regulatory planning (drafting outcome-based regulations and guidelines) and the pilot noted above. In the meantime, the FFV sector has developed its own establishment safety system program, known as CanadaGAP. The development of CanadaGAP illustrates a recognized need by industry for FFV safety programs and measures. CanadaGAP is recognized by the Global Food Safety Initiative and the CFIA. The existence and high level of voluntary adherence to the CanadaGAP represent an opportunity for the CFIA to co-ordinate its preventive control plans and overall risk-management approach with stakeholders, as the Agency seeks to significantly expand its food safety oversight for FFVs.

Outside of the FFVP, the CFIA provides support for the development of preventive control plans, like HACCP, through the On Farm Food Safety Recognition Program. This Program is funded by AAFC and delivered by the CFIA. It formally recognizes on-farm food safety systems that industry has developed and implemented and that meet the regulatory and program requirements. The Program has completed its Part One Technical Review of CanadaGAP at the time of this evaluation and anticipates an application for full recognition shortly.Footnote 31 In this way, the CFIA has influenced industry food safety by supporting an industry led self-credentialing system. CanadaGAP is also one of the few associations that have begun their assessment application process for the more nascent Post Farm Food Safety Recognition Program.

As noted above, the FFVP's safety monitoring has been minimal so information on compliance is insufficient to assess achievement of food safety outcomes. However, while the targeted studies under the Food Safety Action Plan have indicated strong overall compliance, they have also identified commodities through imports with worrisome results. There is an indication that risks may exist in less tested commodities involving rarer, though highly consequential sensitivity reactions. As yet unreleased FSAP results reveal contraventions of requirements under the Canadian Food and Drug Act. While this is only one finding, it suggests that some importers are ignoring Canadian residue regulations in areas not frequently tested.

Quality and Market Access

As previously noted, the quality and market access components of the FFVP took up the bulk of the operational resources during the review period and represent the key historical basis of the Program. There are 30 produce commodities for which grade standards have been prescribed under Section 3 (1) of the FFV Regulations (See Annex A). Most of these were established in the 1930s. However, only four products now require inspections (apples, potatoes, blueberries and onions). Despite this significant decrease in products subject to regulatory grading coverage, the FFVP is not able to meet the requirements in many instances.

As noted in Section 3.1.1, the Agency's use of "Y" releases as the rule instead of the clearly intended exception strongly suggests that the marketing support function is under-resourced to meet regulatory and Program requirements.

There is also a grade inspection requirement for potatoes, onions and field tomatoes traded with the U.S. A reciprocal agreement allows Canada and the U.S. to accept certificates from each other that verify grade requirements. There are close to 20,000 inspections required annually of the CFIA for the export of these products to the U.S., making these inspections the single largest resource cost for the FFVP.Footnote 32

There are programs within the FFVP that have been established to ease the grade inspection burden. The Registered Produce Warehouse Program (RPWP) allows products to move between provinces without the need for mandatory quality inspections on each outbound load. The purpose of the RPWP is two-fold: to provide industry with the flexibility to ship produce without waiting for an inspector; and to reduce the CFIA's resource requirements by reducing the number of shipping point inspections. There are 90 potato and apple establishments in this program.

Under the RPWP, registered establishments must demonstrate the continued ability to pack product to quality standards. The frequency of the inspector's verification of this is based in part on the compliance history of the establishments. This amounts to one Program planned inspection per week for some establishments, and as little as one per month for those with good systems and history. However, limited FFVP resources mean that the average number of inspections per establishment is usually less than once every two months, as shown in Table 8 below.

The table illustrates that in 2010-11, the average number of inspections per establishment per year was less than 4. This number has since risen to more than 6.5, demonstrating a greater level of delivery on this quality inspection requirement. Note, however, that the Agency's Performance Measurement Framework has a target of 100% for "percentage of inspections of registered fresh fruit and vegetable establishments versus planned". (The RPW system is one example of the FFVP's limited experience with establishment inspections, though these are not related to food safety but rather to a service function to confirm compliance with quality standards.) The Agency's only safety-related enforcement experience comes from the 2010-12 pilot referenced earlier, aside from recalls, intensified sampling and post-incident inspections and verification of corrective actions.

The table below shows the average number of RPW inspections per establishment per year. Following the standard of one to four inspections per month outlined above, the minimum number of inspections per establishment per year would be 12 (if all establishments were inspected only once a month, i.e. if all establishments had the highest rate of compliance).

Table 8: Average Number of RPW Inspections per Establishment per YearFootnote 33

| Fiscal Year | # of RPWs | # of Inspections | Average # of Insp/est/year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 90 | 346 | 3.84 |

| 2011-12 | 90 | 487 | 5.41 |

| 2012-13 | 90 | 591 | 6.56 |

Another aspect of the FFVP delivery relating to market access relates to supporting the issuance of Ministerial Exemptions. As noted in the discussion on Relevance (Section 3.1.1), Ministerial Exemptions were seen positively by industry interviewees as a critical support to supply management.

Table 9: Loads of Produce Moving Under Ministerial Exemptions by YearFootnote 34