The National Sheep On-Farm Biosecurity Standard

2. National Sheep On-farm Biosecurity Standard

This page is part of the Guidance Document Repository (GDR).

Looking for related documents?

Search for related documents in the Guidance Document Repository

Each of the Principles in the Standard is presented in the following sections, first in a summary table and then in a more detailed manner.

2.1 Principle 1: Animal Health Management Practices

| Strategy | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Prepare and use a flock health program | A program that describes the flock health regimens and practices is used for day-to-day flock management. It is the basis for monitoring flock health and is a key source when considering flock performance. A biosecurity plan is integral to and supportive of the flock health program. |

| 2. Sourcing sheep | Additions are limited and, when necessary, animals are sourced from suppliers with flocks of known health status. As few sources as possible are used. New stock is isolated upon arrival. |

| 3. Manage sheep that leave and return to the home farm | If sheep are moved off the farm, they have biosecurity practices consistent with their home-farm practices and, upon their return, they are treated as newly-sourced animals. |

| 4. Isolate sick sheep, flock additions and returning sheep | Sheep showing signs of disease are moved into an isolation area away from the healthy flock until the disease has been resolved. Animals brought onto the farm are held in isolation until disease status has been determined or is resolved. |

| 5. Manage contact with neighboring/other livestock | Sheep in the home flock are housed, moved and pastured in such a manner that the risk of contact with neighbouring livestock or other livestock on the farm is addressed. |

| 6. Plan sheep movement through the production unit | Sheep are moved through and within the production unit by pathways that limit their exposure to diseased or potentially infectious animals and materials. Consideration should be given to health status, age and production stage. |

| 7. Implement sheep health protocols for specific situations | Protocols to limit risks of disease transmission are in place for specific production activities, and farm workers understand and employ them. |

| 8. Limit access by pests, dogs and cats, predators and wildlife | A pest control program is in place and its required procedures are followed. Dogs and cats are vaccinated and spayed and treated for diseases of concern. Their access to sheep housing areas and to manure, placentas, deadstock and other potential sources of contaminated material is controlled (e.g. reduce risk of infection with toxoplasma or dog tapeworms). A predator control plan is in place. |

| 9. Implement health standards for guardian and other working animals | Guardian and working animals are vaccinated, dewormed (e.g. tapeworms) and treated for diseases of concern. |

2.1.1 Strategy 1: Prepare and use a flock health program

Summary: A program that describes the flock health regimens and practices is used for day‑to‑day flock management. It is the basis for monitoring flock health and is a key source when considering flock performance. A biosecurity plan is integral to and supportive of the flock health program.

Maintaining a high standard regarding the health of their sheep is a primary goal for all sheep producers, and achieving this goal requires a flock health program with both proactive and reactive capability. A flock health program enables producers to assess risk and take appropriate precautions to prevent and control the introduction and spread of disease. Proactive elements of the plan include providing good quality food and water and suitable facilities for all aspects of production as a foundation for good health and disease resistance.

For common diseases, every farm should have a flock health program that includes the selection of appropriate vaccines and the design of appropriate vaccination and treatment programs. The flock health program is closely linked to the biosecurity plan. Producers and farm workers should be able to recognize abnormal behaviour and diseased animals and to manage them in a way that limits disease transmission. Producers and workers should be aware of zoonotic diseasesand how to respond to them.

The flock health program should also include how to recognize and respond to possible FADs and emerging diseases. In most regions, a flock veterinarian can be contacted to assist in establishing the program and in responding to certain problems. If producers are unsure of how to find a veterinarian with this expertise, they are encouraged to contact their provincial veterinary associations, veterinary colleges and/or provincial agricultural extension veterinarians for guidance.

Producers who do not currently have a flock health program are encouraged to develop a program with their flock veterinarian that includes the principles and elements introduced in the Standard. Those who have a program are recommended to review their programs in the context of this information, and to regularly review and adjust program elements in response to their flock health experience, changes in the flock, and/or changes in any aspect of their operations. A flock health program is designed specifically for each operation.

The biosecurity component of a flock health program will include:

- Monitoring of the flock's disease status through routine diagnostic testing (e.g. fecal egg counts, serological testing) and including post mortems for unexpected or excessive livestock deaths.

- Vaccination programs to control or prevent disease within the flock.

- Metaphylactic / prophylactic medication programs to control or prevent disease within the flock (e.g. deworming, foot bathing).

- Goal setting for health and productivity measures, and monitoring of those measures, e.g. mortality rates of lambs.

- Strategies to introduce new stock or reintroduce returning stock to the flock. This will include isolation of animals with disease or unknown disease status; vaccination to synchronize vaccination status with the flock; prophylactic medications to prevent introduction of specific disease agents; diagnostic testing for disease status as appropriate.

- Decision plan for isolating sheep with disease or unknown disease status, including release from isolation. This includes resident sheep, new introductions and returning sheep.

- Decision plan for euthanasia of sick or suffering animals.

- Treatment protocols for common ailments as appropriate. These protocols will include meat (and when necessary milk) withdrawal periods for slaughter.

- Proper storage of animal health medications and vaccines.

- Proper disposal of animal health medications and vaccines, including used needles and syringes.

- An annual review of the plan including identifying changes in disease status and risk of disease.

- Annual staff training and review of recognition of disease, and protocols for treating disease, including when to contact the flock veterinarian.

Such a Program should be written down. It should be reviewed and reassessed regularly with farm personnel so there is a clear understanding of the expectations of the program and the role of each staff member, and to ensure that the plan continues to meet the needs of the farm. It must comply with the requirements of any relevant public and regulatory programs, including environment, food safety, animal health and animal welfare.

2.1.2 Strategy 2: Sourcing sheep

Summary: Additions are limited and, when necessary, animals are sourced from suppliers with flocks of known health status. As few sources as possible are used. New stock is isolated upon arrival.

When establishing a new flock, producers are advised to seek information and guidance from veterinarians and other sheep information sources, including provincial extension personnel, provincial organizations, geneticists, genetics suppliers, and successful producers, to determine the make-up of the flock. This information will provide direction in acquiring sheep for the flock, and in how to reduce disease risks. Producers are also advised to apply as many as possible of the practices described here when starting a new flock:

- purchasing from suppliers whose flock health is known;

- limiting the number of (different) sources used;

- isolating and observing flock members during the first few weeks of their residence; and

- maintaining separation between the flock and other species with susceptibility to sheep diseases.

Producers are encouraged to raise as many of their own replacement stock as possible (within the limitations of reduction of co-efficient of inbreeding), and to add sheep from other sources only when necessary. Some producers work with a closed flock, meaning that all of the sheep and rams have been born on-site. When genetic diversity is needed, the use of capable and accredited sources for semen and embryos will allow flock additions to be generated on the farm, rather than being introduced as lambs or sheep.

When acquiring additions or replacements for an existing flock, it is recommended that producers know the health status of the source flock, and purchase from flocks with a health status equal to or better than the home flock.

Acquiring sheep from multiple sources, commingling them together, and introducing them into a home flock presents a significant disease risk. The number of diseases that must be accounted for is increased, and treatment protocols required upon entry are expanded. The risk is particularly high when sheep are acquired through an uncontrolled auction market or other commingled sale sites, where the sheep are likely to have been exposed to other sheep and to other species without their having been checked by a veterinarian and/or without providing health records for use in the sale.

Knowing the disease status of individual sheep being purchased and the status of the flock from which it came are key to reducing the risk of acquiring one or more diseases along with an animal. Many diseases are chronic and/or asymptomatic and are therefore difficult to identify at the time of sale or at on-site at suppliers' farms. Asking for individual and flock health information is particularly important, as several sheep diseases may be asymptomatic and/or may not be obvious, and since sheep may be “carriers” of disease. It is also important to know the treatments and/or vaccinations these sheep may have had, in order to establish their compatibility with the receiving flock.

Feedlots that do not keep breeding stock and where, as a result, animals spend relatively little time on-farm, may view some of these disease risks differently. Chronic disease and causes of infectious abortion are less important. Acute diseases of lambs and vaccination status may remain important.

In order to achieve the possible benefits of reduced disease risk in their operations, feedlot operators can ask their suppliers to adopt the practices proposed in this strategy:

- require information on health and vaccination status;

- reduce the number of sourcing points; and

- reduce the extent to which the lambs are commingled.

While suppliers are adjusting to these goals, feedlot operators can implement practices in their own feedlots to reduce the impact of the current level of risk:

- avoiding sales of commingled lots

- isolating groups and/or avoid commingling of lambs when they arrive or while in the lot;

- vaccinating and treating them for the feedlot's diseases of concern; and

- removing them from the feedlot when in doubt.

2.1.3 Strategy 3: Manage sheep that leave and return to the home farm

Summary: If sheep are moved off the farm they have biosecurity practices consistent with their home-farm practices, and upon their return they are treated as newly-sourced animals.

When sheep are taken away from the farm to attend shows and fairs, to graze community pastures, or to be used for breeding purposes, they are frequently commingled with other sheep and/or with other animals susceptible to sheep diseases. They are at risk of becoming infected by any disease pathogens that might be present at that location.

The risk is both from direct contact with animals that might be infected with a disease, and from indirect contact in any of the following ways: from show or farm personnel and/or through contaminated equipment, manure, bodily fluids and/or aerosols on site. These contaminants might be present in feed and water available at the off-farm site, in bedding, on surfaces in facilities in which the sheep are housed, or in vehicles in which they are transported.

As much as possible, the biosecurity requirements of these sheep should be maintained when they are off-farm, and the time of their potential exposure to additional/new risks should be limited. Ideally, flock health status at the off-farm location is compatible with the home farm, and feed, water, bedding and handling equipment can be supplied from the home farm. To minimize risk, sheep that have been off-farm are vaccinated and/or treated for any known or potential risks and are isolated from the maternal flock for a suitable period of time upon their return, as described in the following Strategy.

2.1.4 Strategy 4: Isolate sick sheep, flock additions and returning sheep

Summary: Sheep showing signs of disease are moved into an isolation area away from the healthy flock until the disease has been resolved. Animals brought onto the farm are held in isolation until disease status has been determined or is resolved.

Sick sheep: When a sheep is diagnosed or suspected of suffering from an infectious disease, or exhibits unusual behaviour that might be associated with disease, it should be isolated from the flock. This can be done by moving the affected sheep to a separate pen that prevents direct and indirect contact with the healthy flock. Alternatively, the healthy animals can be moved away from the sick animal if the environment is considered contaminated. Isolation lowers the risk to other flock members by reducing the possibility of infection from direct, nose-to-nose or aerosol contact. It also allows manure and other potentially-infectious materials to be handled separately, thereby ensuring that contamination of the healthy flock, its tools and equipment and its facilities is minimized.

Introduced and returning sheep: When sheep are brought onto the farm or returned from off the farm, they should be isolated from the flock in an area(s) that is located and managed separately from the rest of the farm. The isolation area reduces the potential risk of disease transmission from the isolated animals to the rest of the flock, both by direct and indirect means; isolated animals do not commingle with the rest of the flock, and the risk from people, tools and equipment is managed by cleaning and disinfection practices. The area will also allow isolated sheep to be regularly observed, so that uncertain disease status can be clarified, either when clinical signs do or do not develop, or by disease testing, and so that vaccination and treatment can be applied on an individual basis.

It is important to note that there are limits to the effectiveness of isolation for sheep. Some sheep diseases will not display visible clinical signs during limited isolation and are not reliably diagnosed by testing. These include Johne's disease, orf (soremouth), caseous lymphadenitis, pinkeye, and several abortion agents. This list is not exhaustive. Sheep (and other livestock) can carry many disease agents without suffering from them, but they can be transmitted to other animals; again, the disease may not be revealed during a stay in isolation.

It is also important to realize that sheep are social animals and that individual isolation may result in degradation of the isolated sheep's health status, independent of its specific or suspected disease status. Mirrors mounted outside the pen gate will provide an image of a companion and can be used when single sheep are isolated.

2.1.5 Strategy 5: Manage contact with neighboring/other livestock

Summary: Sheep in the home flock are housed, moved and pastured in such a manner that the risk of contact with neighbouring livestock or other livestock on the farm is addressed.

Sheep in many flocks will be pastured regularly during the course of their production cycles. This means they will be moved from fully- or partially-enclosed areas of the farm to open pasture, between pastures, and back again during these periods. This process introduces the potential for contamination of the flock from contact with other animals on the farm, with wildlife or with flocks on adjacent farms. In particular, introducing pathogens into an enclosed environment during these cycles is a significant risk due to the concentration of the flock.

Addressing the biosecurity risks of pastured sheep requires consideration of a number of factors:

- The disease status and biosecurity practices of other livestock on the farm, especially goatsFootnote 4; if other livestock on the farm are not subject to the same level of biosecurity, then the biosecurity plan for sheep may be compromised;

- The disease status of sheep and other animals on adjacent farms and the biosecurity practices undertaken on them;

- The method of spread of some sheep diseases, for example the aerosol/airborne transmission of Q Fever, that cannot be managed or avoided outdoors and diseases that can be spread by nose-to-nose contact;

- Potential contact by pastured sheep with contaminated materials in the pasture, in waterways, or along common fences, etc.

- The specific diseases that are likely to be spread or carried by wildlife, such as rabies, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Paralapostrongylus tenuis (deer meningeal worm) and Fascioloides magna (deer liver fluke).

2.1.6 Strategy 6: Plan sheep movement through the production unit

Summary: Sheep are moved through and within the production unit by pathways that limit their exposure to sick or potentially infectious animals and materials. Consideration should be given to health status, age and production stage.

Movement of sheep is quite frequent during any production cycle, and some movement, such as milking, moving lambs and sheep to the loading area for transport, and moving sheep to and from pasture are quite repetitive. Others, such as moving older animals, moving new introductions to isolation, moving sick animals to the treatment area or moving rams and ewes for breeding, are less frequent and less regular. In all these cases, movement of sheep within the production unit provides a mechanism for these animals to spread any disease organisms that may have been introduced elsewhere in the facilities. Other members of the flock, using the same pathways, are at risk to being infected by them. These risks are usually higher within the barn or small paddock areas, given more limited space and higher frequency of use, and when considering more frequent movements.

The design/identification of pathways along which sheep and lambs will travel can be an important part of a biosecurity plan. Unless new facilities or renovations are planned, producers will use existing paths and corridors and can adjust for the potential risk by implementing other practices. These alternative actions will include scheduling and order of animal movements, and cleaning and disinfection between uses, where appropriate.

2.1.7 Strategy 7: Implement sheep health protocols for specific situations

Summary: Protocols to limit risks of disease transmission are in place for specific activities, and farm workers understand and apply them.

Proactive biosecurity, designed to reduce the risk and avoid the occurrence of a disease, should include flock health protocols for specific situations. Specific flock health protocols should be considered in production activities such as lambing, abortion management, milking, disease testing, vaccination, and parasite control. Specially-designed protocols are also likely to be required on each farm to address certain diseases of concern.

It is important that producers think about these activities when biosecurity plans are being developed, and when flock health management is considered. Farm workers should understand the approaches to be taken when they encounter these special cases, in addition to understanding the more generalized biosecurity practices.

2.1.8 Strategy 8: Limit access by pests, dogs and cats, predators and wildlife

Summary: A pest control program is in place and its required procedures are followed. Dogs and cats are vaccinated and spayed and treated for diseases of concern. Their access to sheep housing areas and to manure, placentas, deadstock and other potential sources of contaminated material is limited. A predator control plan is in place.

Pests, dogs and cats, predators and wildlife represent a pool of unique risks to sheep. They are difficult to fully control, but do require attention in a biosecurity plan. In many cases very specific actions to avoid direct and indirect transmission of pathogens can be taken.

| Agent | Nature of Risk |

|---|---|

| Pests (e.g. rodents, flies, other insects) | Transmission of pathogens by prior contact with other animals, manure, placentas, deadstock, etc.; direct interaction with sheep and contamination of feed, in storage or in feed bunks, and water |

| Dogs and cats | Infection with diseases of concern on the farm (e.g. rabies); transmission of pathogens by prior contact with other animals, manure, placentas, deadstock, etc.; direct interaction with sheep and contamination of feed and water |

| Predators | Direct attacks on sheep and lambs |

| Wildlife | Direct or indirect contact, including invasive contact by rabies‑infected skunks and raccoons |

It is important to note that dogs are frequently employed for herding and guarding in pastures. Limitation of their involvement is not being recommended here; rather that there is concern for transmission of rabies and possible contamination of sheep and/or facilities with pathogens by physical means.

2.1.9 Strategy 9: Implement health standards for guardian and working animals

Summary: Guardian and working animals are vaccinated, dewormed (e.g. tapeworms) and treated for diseases of concern.

Guardian and working animals are essential to the operation of many farms and to the well‑being of the flock when sheep are pastured during any phases of production. Their health needs to be actively managed and they need to be protected from the risks that are a natural part of their environment. Specific risks associated with guardian animals and other working animals around the farm include rabies, tapeworms (sheep serve as intermediate hosts for the dog tapeworms), and ascarids that can migrate from dogs and become situated in the livers of sheep.

2.2 Principle 2: Record Keeping

| Strategy: | Summary: |

|---|---|

| 1. Maintain and review farm records | Farm records for production, operations, animal health and biosecurity are integrated together. Records include goals, analysis of the records to determine current flock status and strategies to reach goals, and are reviewed regularly. Records of health events and diagnostic test results are used both to initiate interventions and changes to the flock health program, and are important when selling animals to other producers. |

| 2. Record education and training activities | Records of education and training of farm workers are important both for internal farm purposes and to ensure that information potentially required for labour standards is available. |

| 3. Develop a Response Plan For Disease Outbreaks | A response plan is needed to guide farm activity in rapidly‑developing and large-scale changes in health status. Enhanced biosecurity will be required and a recovery plan needs to be prepared. |

2.2.1 Strategy 1: Maintain and review farm records

Summary: Farm records for production, operations, animal health and biosecurity are integrated together. Records include goals, analysis of the records to determine current flock status and strategies to reach goals, and are reviewed regularly. Records of health events and diagnostic test results are used both to initiate interventions and changes to the flock health program, and are important when selling animals to other producers.

Biosecurity and animal health records should be maintained together with other flock and production records. Viewing production records together with movement, health and treatment records will provide a more complete understanding of flock performance; this, in turn, will enable valuable analysis of the impact of biosecurity practices to be done.

It is useful for producers to set goals for the health and productivity of the flock. Analysis of the farm records with respect to disease and treatment rates, productivity, diagnostic testing and results of certain practices are useful when looking ahead to future seasons. A review of these records with the flock veterinarian is recommended on a regular basis. Analysis and conclusions can be compared to the farm's goals, and plans can be altered to achieve the maximum benefit.

Records have low value if they are not reviewed regularly. They are also a valuable resource when an unforeseen situation or event is encountered – these historical records may contain some information that will aid analysis and understanding of the cause.

2.2.2 Strategy 2: Record Education and Training Activities

Summary: Records of education and training of farm workers are important both for internal farm purposes and to ensure that information potentially required for labour standards is available.

Farm records should contain the education and training undertaken by all family members and farm employees (see also section 2.4.4). In some provinces and regions, more attention is being paid to the training and education of employees, especially in areas of public health and workplace safety. While it is also recognized as a good operating practice, under some regulations, producers as employers need to maintain records of training given to employees.

In particular, increasing concern for zoonotic diseases, including Campylobacter, Salmonella, Cryptosporidium, orf, Q fever, abortion and diarrhoea agents, make records of farm worker education on personal protective behaviour, cleaning and disinfection, and other biosecurity practices essential.

2.2.3 Strategy 3: Develop a Response Plan for Disease Outbreaks

Summary: A response plan is needed to guide farm activity in rapidly-developing and large‑scale changes in health status. Enhanced biosecurity will be required and a recovery plan needs to be prepared.

The Standard is focused on proactive biosecurity – those practices that can be adopted to reduce the risks of disease occurrence in many aspects of sheep farming. However, it is important that producers also have a farm-based plan for response to a disease outbreak or the suspicion of an outbreak on their farm or in their region.

A response plan is a pre-determined set of actions and conditions that are enacted when one or more occurrences, called “trigger points”, are observed. The plan is developed in advance, and will include:

- preparatory steps to be taken before an outbreak occurs;

- identification of potential trigger points; and

- enhanced biosecurity protocols to be initiated on the farm under specific circumstances.

In developing such a plan, producers will need to identify the types of disease emergencies that may require a response. These could include:

- an uncontrolled outbreak of any highly infectious disease on the producer's farm, such as an abortion outbreak,

- an uncontrolled outbreak of any highly infectious disease such as a salmonellosis outbreak in the region of the producer's farm;

- a suspected case of a reportable disease or FAD on the producer's farm,

- a suspected case of a reportable disease or FAD on an adjacent farm, or on a farm that has a link to the producer's farm; and

- a confirmed case of a reportable disease/ FAD/ emerging disease anywhere in the region, and especially on a farm with which the producer's farm has exchanged animals, loaned equipment, used shared pasture or other facilities.

Producers must know what they are to do in each of these emergency situations. It is also important that a recovery plan be in place as the next action following execution of the response plan. While recovery efforts are often disease-specific and therefore difficult to plan in advance, producers need to know what is required to be done in order to return to full production once the disease emergency has been successfully managed.

Development of an on-farm “Response Plan for Disease Outbreaks” is a large and complex undertaking; more than can be dealt with effectively in this document. However, information concerning risk management practices to apply in an emergency situation is provided in the Guide and examples are available from various organizations via the Internet, from federal and provincial government agencies and from industry associations.

2.3 Principle 3: Farm, Facilities and Equipment

| Strategy: | Summary: |

|---|---|

| 1. Create a diagram of the farm layout and identify risk areas | A farm diagram is used to assist in the risk assessment, based on the diseases of concern. |

| 2. Clean and disinfect facilities, equipment and vehicles | Cleaning and disinfection methods that are effective in reducing the risk of disease transmission are in place and are used for facilities, equipment and vehicles on the farm. |

| 3. Reduce risk in barns/pens | Facility design and management practices reduce specific risks. |

| 4. Reduce risk from equipment | Equipment can be dedicated for one purpose or dedicated for use in one risk area; equipment can be supplied by the farm for use by contracted service providers. |

| 5. Reduce risk from vehicles | Vehicle use patterns determine the relative risk of vehicles; cleaning and disinfection are the principle biosecurity tool for reducing vehicle-related disease risk. Using farm-based vehicles can improve producers' control over vehicle use patterns. |

| 6. Manage manure | Manure is removed regularly and moved in a manner that limits exposure to the sheep. Tools and equipment used for manure handling are not used for feed or bedding and they are cleaned and disinfected between uses. Storage is secure and separated from the production area(s). Distribution is controlled. |

| 7. Manage feed, water and bedding | Feed, water and bedding serve to support sheep health and therefore the flock's resistance to disease. Adequate and quality supplies are required, and storage is secure from contamination. |

| 8. Apply shearing protocols | Order of shearing is important to reduce the risk of disease transmission within the flock; equipment should be cleaned and disinfected between groups when health status is different, and contract shearers should wear clean outerwear and cleaned and disinfected footwear when they enter the premises. |

| 9. Manage needles and sharps | Needles and sharps should not be re-used; if they are re-used, an assessment is conducted to evaluate the risk. Reusable needles are available for use in multi-dose injection syringes. Proper injection practices are followed and sharps are disposed of appropriately. |

| 10. Manage deadstock | Deadstock are removed immediately from livestock rearing areas and moved in a manner that limits cross-contamination with the flock. Placentas, aborted material and other tissue are managed as deadstock. The deadstock holding area is located away from the production area and is secured against dogs, cats and scavengers. Disposal respects local regulations and is done in a manner that limits disease exposure to the flock. |

2.3.1 Strategy 1: Create a diagram of the farm layout and identify risk areas

Summary: A farm diagram is used to assist in the risk assessment, based on the diseases of concern.

Biosecurity plans are based on a risk assessment of the farm's operations, the people on the farm, providing service or visiting the farm facilities. An accepted approach to risk assessment is to consider the diseases of concern to the farm, and to document how those diseases are known to be transmitted. Then, identify where risk points exist in sheep operations, people's activities, and facilities and how they are maintained. Risk points in this context are where disease pathogens could be transmitted, both directly to sheep and also indirectly to sheep via other fomites.

The use of a map or diagram of the farm layout is recommended to facilitate the identification of these risks. The diagram can highlight areas of specific activity where sheep of different disease susceptibility might be exposed to one another; where people, their tools and equipment and their vehicles might come in contact with the sheep; and where contaminants might be harboured in any parts of the facilities themselves.Footnote 5

Areas that would be highlighted on the farm diagram include:

- Access points

- Gates and barriers

- Location of signage

- Home area

- Farm buildings, including barns, sheds, service areas, farm office and utility areas

- Pens and isolation areas

- Animal loading and unloading area

- Feed storage area

- Manure storage area

- Deadstock pickup area or compost location

- Driveways and lanes

- Parking areas

- Receiving and shipping area(s); the loading chute

- Fuel delivery/storage area

- Paths and walkways

- Pastures

- Wells and other water sources

- Housing and pasture areas for other farm animals

Notes about movement of sheep and other animals around the farm, patterns of access by people and equipment, housing areas for sheep with different disease status, and storage areas for feed, bedding and equipment, can all provide a framework for the practices that might be needed to avoid or reduce the impact of the identified risks.

2.3.2 Strategy 2: Clean and Disinfect Facilities, Equipment and Vehicles

Summary: Cleaning and disinfection methods that are effective in reducing the risk of disease transmission are in place and are used for facilities, equipment and vehicles on the farm.

Cleaning is a constant activity on a livestock farm and disinfection is needed under certain circumstances, especially in dairy facilities and when required to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Cleaning the barn(s), pen areas, feeders, waterers, equipment and vehicles is required to remove organic material that can harbour disease pathogens or other contaminants; disinfection is required to eliminate pathogens. Chemicals used to disinfect are not effective if the surface has not been previously thoroughly cleaned of organic matter.

Five basic steps have been developed for cleaning and disinfecting on farms. They are:

- De-bulking – removing visible contamination including all organic material (e.g. manure, bedding, soiling of walls, floors and equipment)

- Washing – washing with soap/detergent and water

- Rinsing – removing all soap residue

- Disinfecting – soaking with an approved disinfectant

- Rinsing (if required by disinfectant product) – removing all disinfection and allowing surfaces to dry

Feedlot operators, and others who might be concerned about the biosecurity risk in pasture areas, can also employ a downtime cycle between uses – a period of time without animals in the pasture area(s), pens, and other working areas – that is long enough to allow specific disease agents to be reduced by natural death – and will vary depending on the disease agent of concern. This will further reduce the level of contamination before introducing new animals or groups of animals. However, some organisms will live for months (e.g. orf virus, parasite larvae, and the bacteria that causes caseous lymphadenitis) to years (e.g. the bacteria which causes Johne's disease, coccidial oocysts) to even longer (spores which cause anthrax, blackleg and pulpy kidney).

Cleaning and disinfection should be planned to address the farm's identified risks, and a protocol should be designed for the cleaning and disinfection required in each case – for equipment, for example. This will require a clear understanding of how to properly remove organic material from the surfaces that need to be cleaned on each piece of equipment, and when use of a disinfectant is appropriate.

Protocols are required that assure effective cleaning and disinfection of the following facilities and equipment on a sheep farm:

- Barn surfaces, including floors, pens, railings, chutes, walkways, etc. and all areas of the milking parlour;

- Equipment, such as tractor/skid-steer buckets, forks, shovels, tires, etc.;

- Feed storage areas and bins, to eliminate contamination from rodents and other pests, and any manure or faeces that have been deposited in feed bunks or other feeders;

- Water troughs and bowls, to eliminate contamination from any manure or faeces that have been deposited there;

- High risk vehicles, such as those that transport sheep and other animals, especially sheep and animals from other locations; and

- Other vehicles, such as visitors' and service providers' vehicles, especially those that have driven on other farms.

2.3.3 Strategy 3: Reduce risk in barns/pens

Summary: Facility design and alternate management practices reduce specific risks.

Most practices that are contained in biosecurity plans for sheep farms are designed to reduce the risk of disease transmission between animals and from people and their tools, equipment and vehicles to animals. In addition to these activities that act more directly on the disease risks, there are also important options to consider in developing a plan.

The design and construction of facilities that house sheep can be modified to support other biosecurity practices and/or to address risks directly. For example:

- smooth, non-porous materials or finishes can be considered that both reduce the ability of organic materials and pathogens to adhere to surfaces, and make the surfaces more effectively cleanable.

- the design of the facility can reduce the distance and reduce steps in removing manure from the barn(s) and other facilities,

- divisions between pens or lots can be easily removed to allow for easy access of cleaning equipment,

- floor surfaces can be designed to be more easily cleaned,

- in meat operations, barns can be subdivided to separate groups of animals so that they are less likely to cross-contaminate.

Also, some production practices can be introduced that reduce the disease risk under certain circumstances where biosecurity practices are difficult or impractical to implement. For example, when meat production is being planned, either on a feedlot or full-scope production unit, a form of all-in-all-out scheduling can be used to limit potential commingling of current and added stock. If lambs can be managed in groups by purchase sequence or production lot, and the groups kept separate from one another, they are less likely to transmit disease to all of their flock-mates, thereby limiting the potential production losses to smaller groups.

2.3.4 Strategy 4: Reduce risk from equipment

Summary: Equipment can be dedicated for one purpose or dedicated for use in one risk area; equipment can be supplied by the farm for use by contracted service providers.

Cleaning and disinfecting equipment between uses is a mainstay of a biosecurity plan, and can address the risk of disease transmission both within a production area and when equipment is used in multiple production areas and for multiple tasks around the farm. However, there are additional approaches that can be used to reduce the risks attendant to the use of equipment on the farm. Examples include:

- Equipment dedicated to certain purposes – for example, loader/skid-steer buckets used only for deadstock or manure or feed management; forks used only for feed or manure;

- Equipment dedicated to use in one risk area – for example, forks that are used only in the isolation area;

- Equipment that is provided by the farm, rather than by service providers – for example, hoof-trimmers, shearing equipment, and handling systems.

2.3.5 Strategy 5: Reduce risk from vehicles

Summary: Vehicle use patterns determine the relative risk of vehicles; cleaning and disinfection is the principle biosecurity tool for reducing vehicle-related disease risk. Using farm-based vehicles can improve producers' control over vehicle use patterns.

Vehicles used for different purposes and coming from different sources represent different risks to the farm. Risk factors for trucks and trailers include:

- carrying multiple products – for example, sheep, other livestock, feed, manure, and deadstock; and

- travelling to multiple farms and other livestock facilities, including abattoirs, auction markets and shows.

The main concern is that producers often do not know what potential disease risks are presented by trucks arriving on the farm – what they have carried and where they have been.

Vehicles are at lower risk when they are used solely to carry people to and from the farm and do not have direct contact with animals or high-risk products such as manure or deadstock. However, these vehicles may require biosecurity practices if they travel from farm to farm or between the farm and other livestock areas – abattoirs, auction markets and shows, for example.

Cleaning and disinfection is the principal means to manage the risk related to vehicles. Inside the box or trailer are critical if sheep are being transported. The exterior of the vehicle is important if it travels across pathways taken by animals or into areas containing contaminated material that could infect other areas of the farm. The interior of the cab is a concern if the driver or passenger(s) must leave the cab and enter any area of the farm that is accessible by sheep.

During times or in locations in which washing and disinfection are not possible (e.g. extreme cold weather), it is important to understand the risk of the contaminated equipment and manage it to reduce exposure of livestock to pathogens present.

One alternative is to use only vehicles whose use is controlled by the farm. This removes the uncertainty of third-party vehicles and allows the producer to manage the biosecurity practices that are applied. Carrying sheep in a farm vehicle also has the advantage of common disease risk between the vehicle and the farm. If a third party vehicle must be used, load animals away from livestock rearing areas and do not allow the vehicle to cross any part of the premise where livestock or equipment used to manage livestock might be kept.

2.3.6 Strategy 6: Manage Manure

Summary: Manure is removed regularly and moved in a manner that limits exposure to the sheep. Tools and equipment used for handling manure are not used for feed or bedding and they are cleaned and disinfected between uses. Storage is secure and separated from the production area(s). Distribution is controlled.

Manure management includes addressing risks for removing manure from the production area, movement on the farm, storage on farm, and eventual disposal/distribution on land.

Manure should be removed from the pens or holding areas regularly, determined by the number of sheep housed in each area, and more frequently if there is any concern of disease in the pen (bedding should also be removed, the pen cleaned and disinfected, and the bedding replaced in these cases).

Manure storage should be away from the production area and be secured from access by farm animals. Its location should therefore be away from the production area(s) and situated such that runoff will not accumulate and will not contaminate livestock rearing areas, pastures, wells, feed storage or other service areas. Most local jurisdictions will have regulations for manure storage and compliance is required.

Movement off-site, if planned, requires care in accessing the storage area, respecting farm zoning practices, and avoiding spillage or other contamination of farm areas upon exit. Disposal on the farm property – composting and/or distribution on fields and pasture – will follow requirements of the environmental farm plans and nutrient management programs in effect in each area.

2.3.7 Strategy 7: Manage Feed, Water and Bedding

Summary: Feed, water and bedding serve to support sheep health and therefore the flock's resistance to disease. Adequate and quality supplies are required, and storage is secure from contamination.

Carefully managing feed and water is important to provide a strong health foundation in the flock. This health foundation improves the ability of sheep to resist disease organisms and toxins.

Both home-grown and purchased feed needs to be free of toxins that may naturally occur or that may form in storage; excessive copper remains a significant concern for sheep, as does Listeria bacteria often present in wet ensiled feeds and some mycotoxins. An assessment of the quality and nutritional value of the feed is useful and will guide decisions regarding the addition of supplements or minerals to ensure a complete, healthy ration.

Similarly, clean fresh water in adequate volume should be made available to all stock at all times. Water should be tested at least annually and as required by local/regional regulation to ensure its cleanliness and safety. Its source location and facility should be checked to ensure that there is no contamination from surface water or runoff.

Bedding material storage practices are different by regions and by available facilities on farms. Ideally, when weather conditions require it, bedding should be stored in a protected location such that it remains dry and uncontaminated. As much as possible, bedding material should be secure from contamination by pests, dogs and cats, and rodents. Bedding material in use should be judged by its moisture and cleanliness, cleared regularly, and replaced by dry, clean product.

2.3.8 Strategy 8: Apply Shearing Protocols

Summary: Order of shearing is important to reduce the risk of disease transmission within the flock; equipment should be cleaned and disinfected between groups when health status is different, and contract shearers should wear clean outerwear and cleaned and disinfected footwear when they enter the premises.

On some farms shearing is carried out by producers themselves, or farm workers, using the farm's equipment. On other farms, shearing is done by contract shearers who are expert at their craft, who travel from farm to farm, and who bring with them equipment that is well-suited to the task. Clearly, while there are benefits to both approaches, there are different risks that pertain to each.

Shearing by producers or farm workers presents the risk of disease transmission from one sheep to another from equipment that is not sufficiently cleaned and disinfected between uses. This risk is heightened by the possibility of nicks and skin abrasions, and the added opportunity of disease transmission by blood or other fluids from or into the nick. For example, the bacterium that causes caseous lymphadenitis CLA), a common sheep disease causing abscesses of the lymph nodes, can invade slightly abraded skin and these abscesses, nicked during the shearing process, provide a very important risk for transmission. Careful attention must be paid to cleanliness and risk avoidance practices during the shearing process to avoid this and other diseases and conditions. Ticks, lice and mange mites can be similarly transmitted by shearing.

Generally, sheep are grouped/penned in preparation for shearing. There is a possibility of animals coming in contact that usually are in separate areas of the farm, and also a risk of sharing facilities that might be contaminated by one member of the flock. Shearing should start with the lower risk animals and proceed through higher risk animals. If sick animals need to be sheared, they should be done last.

Shearing by a contracted service from off the farm presents all of the risks of producer / farm‑worker shearing, and in addition, the shearer's hands, clothing, footwear and shearing equipment, including shears, bags and boards, all carry the additional risk of being contaminated by disease organisms from other farms. Therefore, contract shearers should wear clean outerwear and footwear and wash their hands upon arrival. Shearing equipment should be cleaned and disinfected between farms, and if conditions like CLA are encountered, changing heads and cutter blades is required.

2.3.9 Strategy 9: Manage Needles and Sharps

Summary: Needles and sharps should not be re-used; if they are re-used, an assessment is conducted to evaluate the risk. Reusable needles are available for use in multi-dose injection syringes. Proper injection practices are followed and sharps are disposed of appropriately.

Reuse of needles and sharps is a high-risk activity as both become contaminated with bodily fluids and blood in which pathogens may be present or grow after use. Both the outside and inside of the needle become contaminated in this manner.

It is not possible to practically and effectively disinfect a needle including its bore; it is therefore recommended that whenever possible, needles should not be reused. The risk of reuse is higher if the needle contains blood, has been used to treat a sick animal, or has sat for any length of time between uses. Risk is lower if needles are used to administer a drug subcutaneously to a series of healthy animals at one time using one product (e.g. vaccination). Reuse of needles increases the risk of injection-site abscesses. Used needles should never be inserted into a vaccine or drug bottle as it will contaminate the product rendering it subsequently dangerous.

Used needles and other sharps (e.g. scalpel blades), should be immediately discarded in a solid‑sided leak- and shatter-proof container that can be sealed and discarded when full.

2.3.10 Strategy 10: Manage Deadstock

Summary: Deadstock are removed immediately from livestock rearing areas and moved in a manner that limits cross-contamination with the flock. Placentas, aborted material and other tissue are managed as deadstock. The deadstock holding area is located away from the production area and is secured from dogs and cats and scavengers. Disposal respects local regulations and is done in a manner that limits disease exposure to the flock.

Deadstock management and management of placentas, aborted material and other tissue address removing deadstock and related materials from the production area, movement on the farm, storage on farm, and eventual disposition. Permitted storage and disposal methods will be regulated under local and regional jurisdiction; each method requires its own biosecurity practices.

Deadstock can contaminate the area in which it is found by body fluids that may contain disease pathogens. These pathogens can find their way into bedding and feed, and onto pasture, and can be contacted and ingested by others in the flock. Placentas, aborted materials and other tissue may similarly contain disease pathogens that can be transmitted to other animals in the flock, to other animals, or to humans. Presence of deadstock attracts scavenger animals such as carrion-eating birds, rodents, cats, dogs and other wildlife. It also attracts flies, which can transmit disease and cause fly-strike.

The pathogens, or material containing them, may be distributed by insects and pests. In all cases, material containing disease pathogens may be moved about the farm or to other facilities by dogs, cats and scavengers, and may also be distributed in their faeces, once consumed.

Therefore, deadstock, placenta and aborted material should be removed immediately when they are seen. They should be stored away from the production area without any access to dogs, cats, wildlife and vermin.

2.4 Principle 4: People

| Strategy: | Summary: |

|---|---|

| 1. Conduct risk assessments for all people entering the farm | All people entering a farm are subject to a risk assessment. |

| 2. Develop and enforce risk management practices for all people visiting the farm, using the risk assessment outcomes | People working on, providing service to or visiting the farm are guided by risk management practices based on the risk assessment. |

| 3. Know what people are on the premises | Producers know who is on the farm, where they are, and what their purpose is. |

| 4. Train farm workers and communicate with them about biosecurity; inform all visitors and service providers | All farm workers and family members are trained in the farm's biosecurity practices. The farm biosecurity protocol is communicated to visitors and service providers and they comply with it. |

| 5. Recognize zoonotic risks | Family members, farm workers, visitors and service providers understand zoonotic diseases and take full precautions to protect themselves. |

2.4.1 Strategy 1: Conduct Risk Assessments for all people entering the farm

Summary: All people entering a farm are subject to a risk assessment.

It is recommended that producers consider a risk analysis of the attendance of all people entering the farm – family members, farm workers, service providers and visitors. This analysis assumes that their attendance at the farm is legitimate and accepted by the producer, and focuses on the specific level of disease risk they represent, based on their previous exposure to farms and to sheep in particular, and the area(s) of the farm they are intending to enter. In the latter analysis, contact with the sheep is considered.

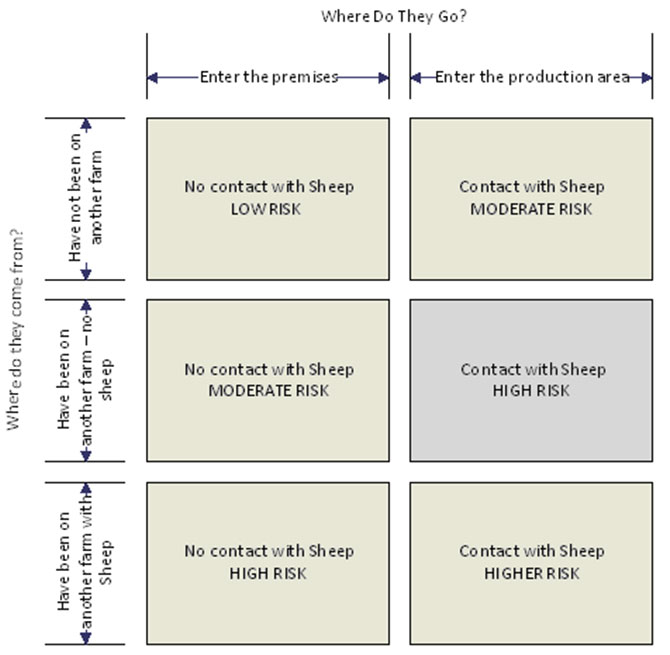

As illustrated in the Matrix below, risk levels can be described as low, moderate and high for simplicity, and can be determined by these factors.

Description of Matrix - Risk Assessment: All people entering the farm

The risk assessment for all people entering the farm is based on their previous exposure to farms and to sheep in particular, and the area(s) of the farm they are intending to enter. A person who has not been on another farm and enters only the premises without having any contact with sheep is considered a low risk for the farm. Someone who has not been on another farm, enters the production area and has contact with sheep is a moderate risk for the farm. A person who has been on another farm, but not a sheep farm and enters the premises without having contact with sheep is considered a moderate risk. Someone who has been on another farm, but not a sheep farm, enters the production area and has contact with sheep is considered a high risk. A person who has been on another sheep farm and enters the premises without having contact with sheep is a high risk for the farm. Someone who has been on another sheep farm, enters the production area and has contact with sheep is the highest risk for the farm.

In general, these groups could be described as follows:

- Low risk: travel to a farm but do not come in direct contact with livestock and do not enter livestock rearing areas; for example, financial advisors and equipment salespersons

- Moderate risk: travel from farm to farm but do not directly contact the livestock; for example, fuel delivery

- High risk: neighbouring producers or anyone who travels farm to farm and comes in direct contact with livestock and have been in contact with livestock from other farms; for example, veterinarians, ultrasound technicians, shearers, and hoof trimmers

- A Higher Risk classification can be considered for anyone who has been in contact with sheep on another farm (or elsewhere), in contaminated facilities or near sick animals. If access to another flock were required, specific risk-reduction steps would be taken.

2.4.2 Strategy 2: Develop and enforce risk management practices for all people visiting the farm, using the risk assessment outcomes.

Summary: People working on, providing service to or visiting the farm are guided by risk management practices based on the risk assessment.

All people entering the farm will be aware of the relative risk of their visit and activities while there. They will know and understand the biosecurity practices that are consistent with that risk assessment, including the areas into which they are permitted to go.

The risk assessment for each individual, based on where he/she is permitted to go on the farm, will determine the biosecurity practices that will be needed upon entry onto the farm and into the production area. A combination of restrictions to access and the requirement for clean hands, clothing and footwear is the basic arsenal for visitors and service providers. A higher level of biosecurity would apply for anyone approaching and/or touching the animals, and higher again for those approaching and/or touching isolated or sick animals.

Pre-determined practices/protocols can be designed that apply to each of these classes of risk, and signs and information can be situated at zone boundaries, on building and pen entries and on special-risk pens to advise visitors where their limits to access are, and when to apply the higher-level practices. Escorting visitors will also help to ensuring that they are following the recommended biosecurity practices.

A special case exists also, concerning people who have visited a foreign country in the recent past that is a known location for a foreign animal disease, and who have had the potential to contact the pathogen. While their relative risk can be established from the matrix described in section 2.4.1, knowing the diseases of concern in the area of the world the person has visited would allow producers to establish suitable delays before visits and to apply specific protocols for visits to Canadian farms. Information on known infectious diseases by country can be sourced from the World Organization for Animal Health

2.4.3 Strategy 3: Know what people are on the premises

Summary: Producers know who is on the farm, where they are, and what their purpose is.

The presence of people on the farm – farm workers, service providers, family members and visitors – represents a significant set of risks to animal health. In a farm biosecurity plan, the following practices are recommended:

- restrict access by people to areas of the farm that require their presence,

- control the conditions of their entry to and exit from those zones and areas,

- require proper management of the tools, equipment and vehicles that accompany them, and

- guide the conditions of their contact with the flock.

In order to ensure that these controls are followed, and therefore that the health and welfare of the flock are maintained, a producer will ideally have full knowledge of who is on the farm at all times. However, many sheep flocks in Canada are managed by producers who might also be employed off-farm. In these cases, security of the facilities and of the flock need to be established by means that operate without the producer's presence, including farm gates and other security features. It is important in all cases for producers to know in advance what service providers and visitors wish to visit the farm, so that they can be instructed in advance or upon arrival in the practices and materials that will be required during their visit.

2.4.4 Strategy 4: Train farm workers and communicate with them about biosecurity; inform all visitors and service providers

Summary: All farm workers and family members are trained in the farm's biosecurity practices. The farm biosecurity protocol is communicated to visitors and service providers and they comply with it.

The success of biosecurity plans will require the involvement and cooperation of several groups and individuals: family members, farm workers, visitors, suppliers, farm service providers and the flock veterinarian.

They will all need to understand the biosecurity best practices that guide their activities on the farm, and will need to ensure that their own biosecurity plans include safeguards that coordinate with the farm plan.

Producers, their family members, farm workers and visitors will benefit from training in the specific biosecurity practices in the Standard, as they are adapted for each farm. Farm service providers will also need to be trained in the practices established for the farms they service, both to ensure that they can carry them out and so that they can accommodate them within their own operational and biosecurity practices.

Effective training and education requires repeated review and/or instruction sessions with the biosecurity information contained in the farm plan, in other literature (a bibliography is provided in Appendix B) and available from subject specialists, advisors and public sources. Information can be provided in group sessions dedicated to biosecurity, on-the-job demonstrations, and corrective actions following one-on-one observations.

2.4.5 Strategy 5: Recognition of Zoonotic Risks

Summary: Family members, farm workers, visitors and service providers understand zoonotic diseases and take full precautions to protect themselves.

Sheep may be affected by a number of zoonotic diseases, such as Q fever, Chlamydia and Campylobacter that can be passed to humans. Family members, farm workers, visitors and service providers need to understand the risks to their own health presented by these diseases and their ability to move between sheep and humans. People can be infected by direct and indirect contact and by aerosol means and a number of protective practices need to be followed that help reduce the risk of disease transmission, including hand washing, and full use of personal protective equipment specific to the disease risk. Personal protective equipment includes coveralls, boots, gloves and masks that are dedicated to working with high risk animals and that can be either cleaned or discarded after use.

- Date modified: